Sometimes a sermon feels half-baked, but that’s all this preacher has this Sunday for a small congregation meeting in the heart of Warwickshire. The focus is on anger, one of the gifts of being human, in the context of violent anti-immigration riots which have been going on in towns and cities in the UK over the last week or so. “Be angry, but don’t let the sun go down on your anger” is the text from the reading appointed for the day – Ephesians 4:25-5:2.

August 11th 2024

See how fearfully and wonderfully made we are. That’s the frame of mind of the Psalmist. We say our Amen when we join the prayer of the psalmist. We are fearfully and wonderfully made. Our Amen is our Yes to this frame of mind and part of our adoration of God. The Psalmist thanks God: “You yourself created my inmost parts. You knit me together in my mother’s womb. I thank you, for I am fearfully and wonderfully made.” (Psalms 139: 12-13)

We don’t just come with our physical make up. We have our psychological make up. We have soul. We are fearfully and wonderfully made – complete with our basic instincts and appetites. Without those instincts and appetites we wouldn’t survive or organise ourselves or build society. The desert fathers listed these instincts so that they could help people discipline them, because without that discipline they turn on us and ruin us.

Among their list of instincts and habits, as an example, is the habit of dejection – which lowers our sights and expects the worst of ourselves. Greed is in that list, and so is anger. They tried to cover all our basic instincts and habits of thought, recognising the demons that turn those instincts against us. They recognise that we all get caught up in corrupt chains of thought that ultimately bind us. You may see that in yourself. I see it in myself. I hear one thing, which leads me to another – it is my doom-looping which has made me bound to think and behave this way and that.

This morning we have a letter to read dating back nearly 2000 years which is dedicated helping to free people from these chains of thoughts and behaviours. It comes to us from the Christians of Ephesus.

Be angry, the letter reads recognising the basic instinct of anger which is part of our make up – part of being fearfully and wonderfully made.

Be angry – why not? Jesus got angry. Our anger can be very useful. Cassian, one of the desert fathers, taught that the proper focus for anger is on our malicious thoughts and on the destructiveness we see around us. These are things we need to get angry about. Imagine a world in which no anger was focused on such things. Imagine ourselves and what we would be like without an anger against some of the ways we are. Anger can make things better.

And anger can make things worse. Anger can turn nasty. Our anger can be deeply hurtful of others and ourselves.

Anger needs reining in. Ephesians has given us a pearl of wisdom which has become almost proverbial. Be angry, but don’t let the sun go down on your anger. I dare say that has saved a good many relationships. Don’t let the angry word be the last word of the day. Don’t take your anger into the night. Keep your anger in the light.

Don’t take your anger into the darkness. Break the chain of thought before the chain of thought traps you in darkness.

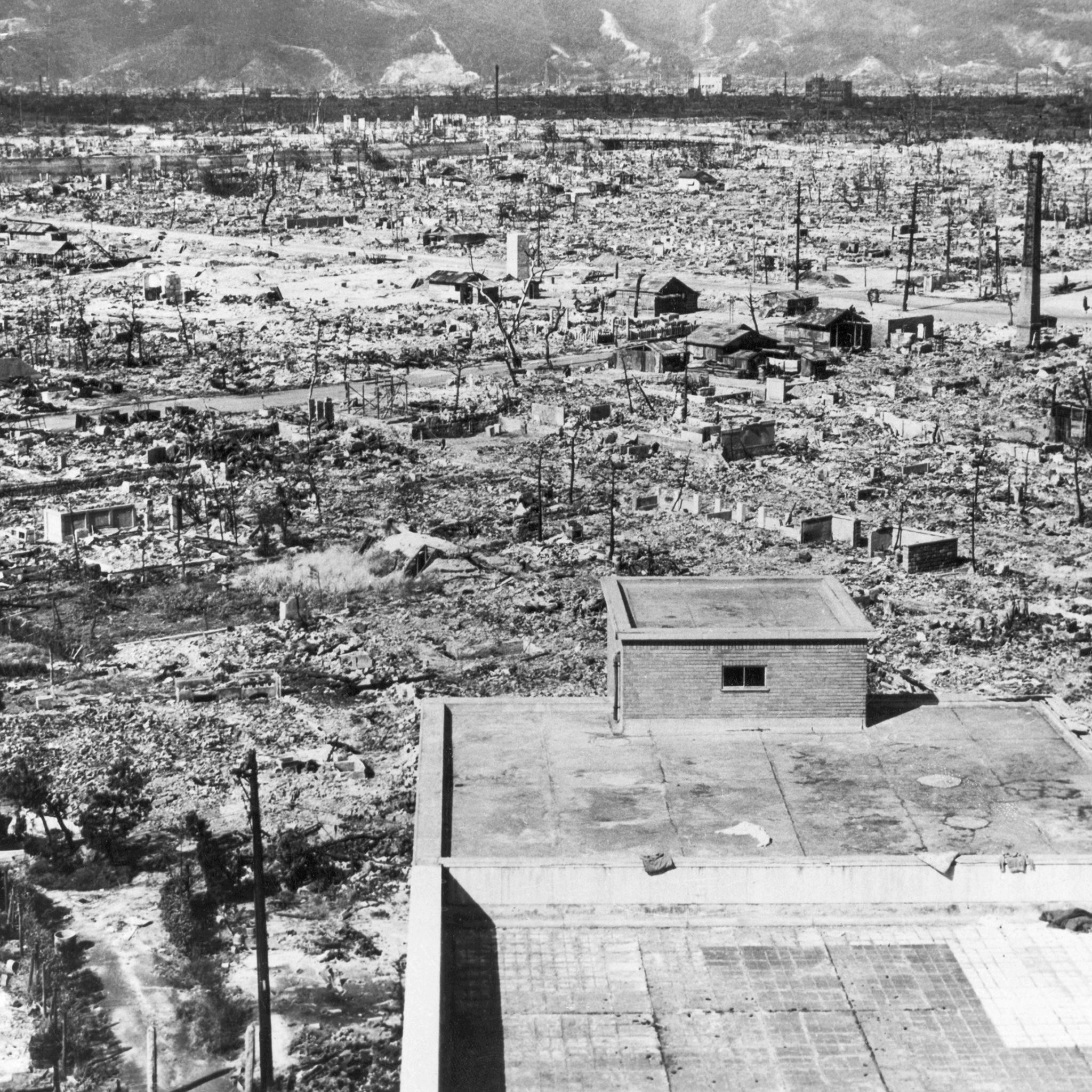

We’ve seen anger spilling onto our streets this last week using mis-information to make targets of immigrants and their defenders, and Muslims and their mosques,

Having read his book The Lightless Sky I’ve been following Afghan refugee Gulwali Passarlay. He featured in the Channel 4 election debate. He posted on Twitter this week that he has “never been this afraid” He’s lived in the UK for 17 years and been a citizen for the last 5. He posted: “I’m afraid for my kids. I to;d my wife, don’t go to the park. I had to travel from Bolton to take my kids to nursery because I was afraid for my wife to walk on the road.” There were NHS staff frightened to go to work. And yesterday I heard that a Faceboog group of British Asians in Leamington were warning members not to go into town because of the possibility of racist attack.

The mob violence we have seen is anger gone wrong – anger pent up, anger that has been taken into darkness by perpetrators who have been misled – and we all need to be very afraid. Thank God for the counter-protesters, and for those who day in and day out defend the stranger and the defenceless.

When we take anger (as well as our other instincts) into our darkness, into the night and into our sleep, we find that, there the darkness spins chains of doomloops to bind us. Anger belongs to the day. Be angry, but be angry in the light of day. The Ephesians tell us, Don’t make room for the devil to work with your anger.

If we don’t make room for the devil to work in our anger we leave room for compassion and love to work there, to direct and discipline our anger.

The permission for anger in Ephesians comes with disciplines that rein in this basic instinct. Putting away falsehood, let all of us speak the truth to our neighbours, for we are members of one another. We belong together. We are made for one another. Anger needs the light of truth, so we only speak the truth to our neighbours and about our neighbours. We’ve seen this week how the incitement to riot relies on falsehoods, deception and misinformation.

In anger, let no evil talk come out of your mouths, but only what is useful for building up, as there is need, so that your words may give grace to those who hear …. Be imitators of God … and live in love.

Anger is one of our instincts. We are fearfully and wonderfully made – with anger and much else. God loves our anger when we are imitators of God. His anger was shown by Jesus. His anger and wrath is against those who put themselves first, the entitled, the supremacists who demean others and put others beneath them and never go to their help. His anger and wrath is against those wolves in sheep’s clothing who lead people astray.

But for those put last, for those lost and misled, for those least, for those forced to flee, for those seeking sanctuary and safety, for those housed in the hotels being attacked in the mob violence, there is only words of love giving grace to those who hear them, and the promise of a rule which puts them first, not last.

Ephesians 4:25-5:2

So then, putting away falsehood, let all of us speak the truth to our neighbours, for we are members of one another. Be angry but do not sin; do not let the sun go down on your anger, and do not make room for the devil. Thieves must give up stealing; rather let them labour and work honestly with their own hands, so as to have something to share with the needy. Let no evil talk come out of your mouths, but only what is useful for building up, as there is need, so that your words may give grace to those who hear. And do not grieve the Holy Spirit of God, with which you were marked with a seal for the day of redemption. Put away from you all bitterness and wrath and anger and wrangling and slander, together with all malice, and be kind to one another, tender-hearted, forgiving one another, as God in Christ has forgiven you. Therefore be imitators of God, as beloved children, and live in love, as Christ loved us and gave himself up for us, a fragrant offering and sacrifice to God.