A sermon for Trinity 20A. I focus on Jesus takes a people bruised and battered by empires to a whole new realm. The readings are printed below. They were Isaiah 45:1-7 and Matthew 22:15-22. It was the emperor in each of the readings which first grabbed my attention.

October 22nd 2023

My Bible

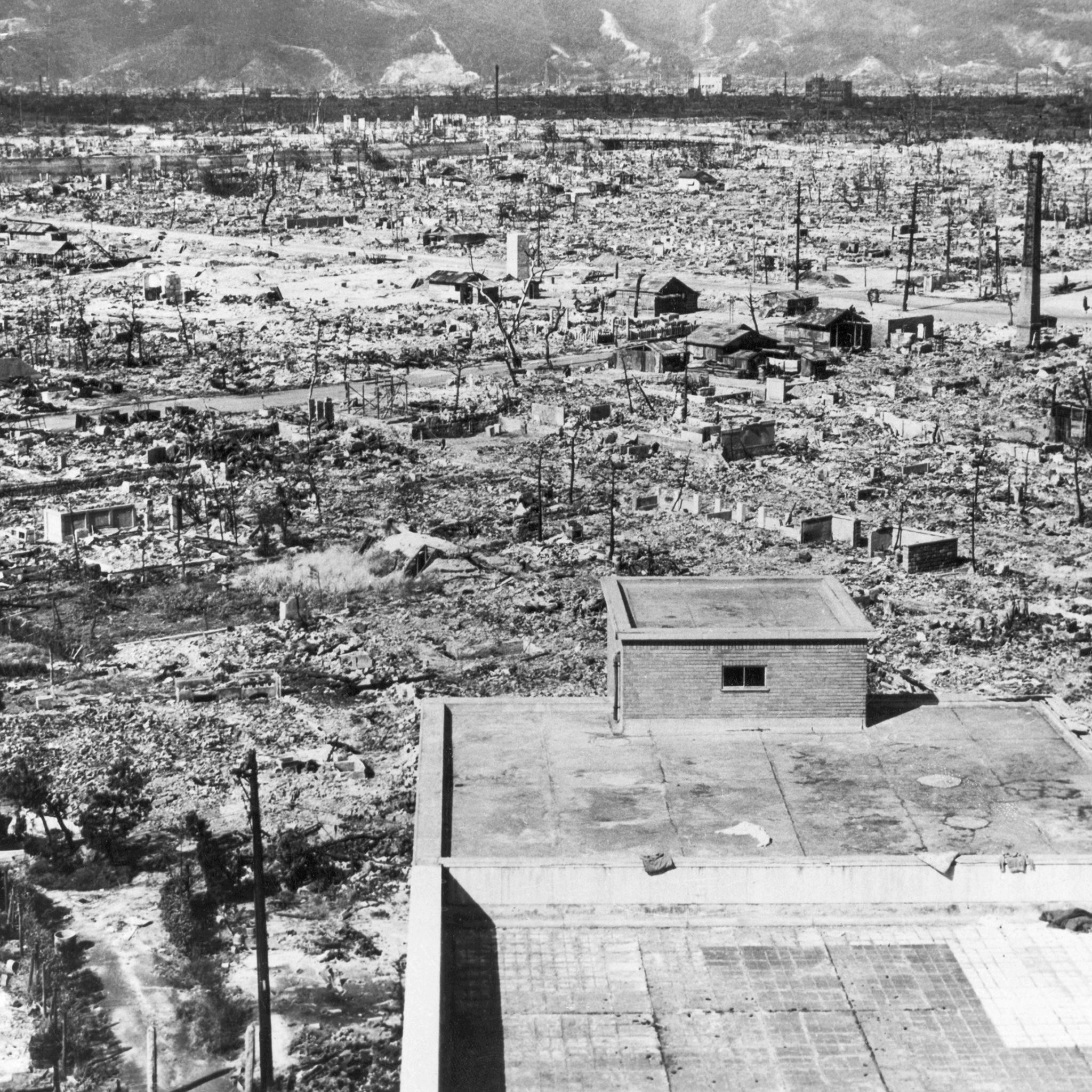

These are the writings of a bruised and battered people who have lived through the worst of times.

This is the reading of a bruised and battered people.

This is their literature. They have treasured it. They have handed it on for the sake of other bruised and battered people.

As always our scriptures are brought to us by a troubled people. It is a troubled people, inspired in the Spirit of God who have chosen the scriptures we inherit and hand on. It is a troubled people who have treasured them and bottled them for us because they have been a a very present help in times of trouble.

They are a people who have had all kinds of suffering inflicted upon them by dominating empires, from slavery in the hands of the Egyptian empire, to destruction of their institutions, to exile, persecution and occupation by the Assyrian, Babylonian, Greek and Roman empires. Their imperial domination, at various times, took their labour, their homes, their institutions, their land, their networks, their lives. Our scriptures give us the very best trauma literature and survival resources.

For those dominated by powers which are not their own there is always the question, “how do we get through this?”

This morning’s readings, brought to us by a traumatised people feature two emperors. In the red corner we have Cyrus whose Persian empire survived a mere 7 years in the 6th century BC. He is the golden boy amongst emperors. He shows us that it is possible for those rich in power to enter the kingdom of heaven by allowing God to take his hand (and arms) to dismantle empire and repair its damage. He is called the Lord’s anointed in our reading from Isaiah – provides a happy and short interlude.

In the blue corner we have the unnamed Caesar, the Roman emperor.

The question the unlikely alliance of Herodians and Pharisees ask Jesus is a trick question. The answer Jesus gives isn’t a simple “pay your taxes”. It’s a trick answer. Pay Caesar what is his. What is his? What is rightfully the emperor’s in a land which he has taken from others. It’s a trick question with a trick answer. Underlying both is that harder question of how do we live with this overwhelming, stifling foreign power?

When we read our scriptures we are always bumping into emperors and hearing of the troubles and damage that they bring. That is the context.

I don’t know whether you will agree with this assessment of our own context – that most of us have shared the benefits and privileges of empire, that we might feel uneasy in the aftermath of empire, uncomfortable about what we might have taken from others and unsure about how we begin to repair the damage.

Empire is always our context. They are built all around us. We may be one of their builders. The superpowers operate imperial models. There are global empires like Amazon and Google (and who should they pay taxes to?) There are the media empires and their hidden persuaders with their bots affecting our habits and views. These are large empires. There are other empires operating the other side of the law – the drug cartels with their barons, the warlords, people traffickers, as well as the little empire builders we see around us. Mr Big always brings favours to some and trouble to many. He is always self serving.

This is our context. And this is the context for Jesus’ teaching about a kingdom and way of life so radically different from the ways of empire. Jesus was tempted by the ways of empire – world domination, stunts and political popularity were not going to be his way. He saw the devil in them.

Instead he helped his followers explore a different realm – a realm in which there is no domination and only amazing grace. To these troubled people Jesus offered an alternative vision of hope. He opens up a kingdom in which everything is small and vulnerable rather than mighty and impregnable.

He casts around for images that we will all understand. To what shall I liken the kingdom of heaven? To people so often belittled by empires, to people who can so easily be lost or disappeared, to a people whose lives are hidden and voice unheard he likens the kingdom to things that are hardly noticed and that can so easily disappear. Like the mustard seed, the smallest of all seeds. Like the leaven folded into the loaf. Like the scattering of seed.

He trains our eye on the birds of the air and the lilies of the field and says there is no glory in empire, nothing like the glory of the lilies of the field. To those who have little, he shows what can be done with little – feeding 4000, feeding 5000.

He turns the world’s rule upside down by saying to those used to coming last that the rule of his kingdom is that the last come first and the first come last. He turns the world upside down by putting children central to the kingdom of heaven, the qualification for entry being that we have to become small and just like a child.

We love to remember that the son of God came to us as smaller than a child, a baby. The teaching he shares is his learning to be a child. In John’s gospel, Jesus teaches that we have to be born again, to seize the opportunity of a second chance of being children.

In that gospel Jesus is just a ray of light that shines in overwhelming darkness, the word of God in edgeways. The words that come to mind when we think of God’s kingdom – if we have learned anything from Jesus – is small and vulnerable.

Maybe it is only as I have retired from the church’s institutions and put some distance between myself and the systems and thinking which mimic the ways of empires and powers, that I have seen, as if for the first time, that the kingdom of heaven is only to be understood in things small, hidden and vulnerable, and that the kingdom of heaven is for those who are the last and least chosen in the kingdoms of this world – for the hidden and vulnerable, and for those who are prepared to make themselves small for the sake of the kingdom.

I have noticed this particularly in this year’s successive gospel readings from Matthew.

At the beginning of his gospel Matthew gives us a name for Jesus, Emmanuel. That name means “God with us”. At the end of his gospel he gives us a promise to remember. “I am with you always, to the end of the age.” He shows the battered, bruised and bloodied people the battered, bruised and bloodied face of Jesus – joined with them in their suffering – and he shares Jesus’s blessing of them.

How blessed are you who are poor in spirit – yours is the kingdom of heaven.

How blessed are you who mourn – you will be comforted.

How blessed are you who are meek – the earth will be yours.

How blessed are those of you who hunger and thirst for righteousness. You will be well satisfied.

How blessed are you who are merciful. Mercy will be shown to you as to no other.

How blessed are the pure in heart. You will see God in the smallest and most vulnerable.

How blessed are those of you who are persecuted. Yours is the kingdom of heaven.

This is the blessing of a bruised and battered community. Today we join them in reading their scripture, in their prayer, in their struggles, in their blessing and in the kingdom prepared for them.

Isaiah 45:1-7

Thus says the Lord to his anointed, to Cyrus,

whose right hand I have grasped

to subdue nations before him

and strip kings of their robes,

to open doors before him –

and the gates shall not be closed:

I will go before you

and level the mountains,

I will break in pieces the doors of bronze

and cut through the bars of iron,

I will give you the treasures of darkness

and riches hidden in secret places,

so that you may know that it is I, the Lord,

the God of Israel, who call you by your name.

For the sake of my servant Jacob,

and Israel my chosen,

I call you by your name,

I surname you, though you do not know me.

I am the Lord, and there is no other;

besides me there is no god.

I arm you, though you do not know me,

so that they may know, from the rising of the sun and from the west, that there is none besides me;

I am the Lord, and there is no other.

I form light and create darkness,

I make weal and create woe;

I the Lord do all these things.

Matthew 22:15-22

Then the Pharisees went and plotted to entrap him in what he said. So they sent their disciples to him, along with the Herodians, saying, “Teacher, we know that you are sincere, and teach the way of God in accordance with truth, and show deference to no one; for you do not regard people with partiality. Tell us then, what you think. Is it lawful to pay taxes to the emperor, or not?” But Jesus, aware of their malice, said, “why are you putting me to the test, you hypocrites? Show me the coin used for the tax.” And they brought him a denarius. Then he said to them, “Whose head is this, and whose title?” They answered, “The emperor’s”. Then he said to them, “Give therefore to the emperor the things that are the emperor’s, and to God the things that are God’s.” When they heard this they were amazed, and they left him and went away.