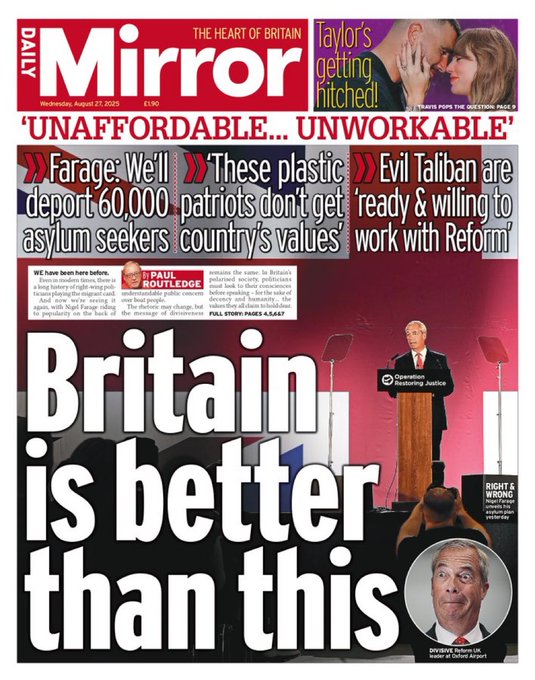

“Britain’s better than this.” That was the headline on the front page of The Mirror last week, after Nigel Farage promised mass deportations in the name of “protecting British citizens.” When the flag of St George is waved as a weapon of fear, Christians must remember another banner — the cross of Christ, where pride is humbled and strangers are welcomed as honoured guests.

“Britain’s better than this”.

That was the headline on the front page of the Daily Mirror on Wednesday.

It followed Nigel Farage’s promise to deport 60000 asylum seekers in a press conference which pressed all the buttons of fearmongering in what seems to be a calculated acceleration of far-right anti-immigration protest and hatred.

In a dogwhistle, the hotels in which asylum seekers are being housed have been identified.

”They’re our hotels” protesters are saying. “Why should they be staying in our hotels free?”

And across bridges and roundabouts, the flag of St George is being draped like a weapon.

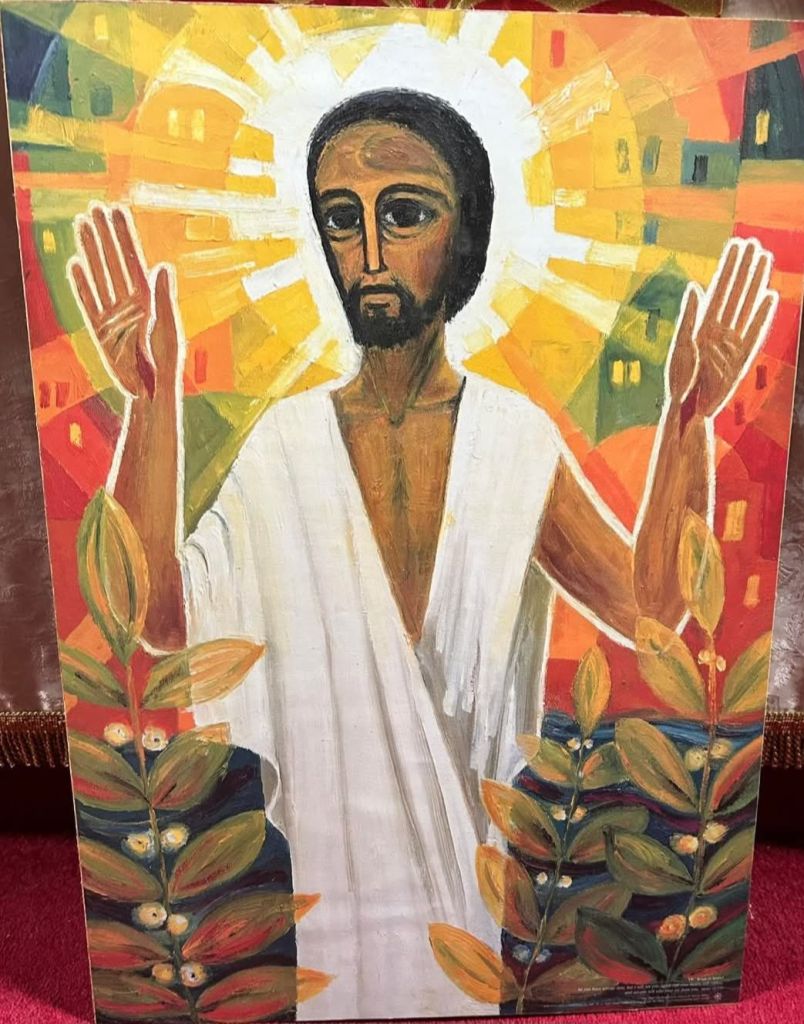

St George, our patron saint.

A Turk, raised in Palestine.

His cross marked by the red cross of faith, echoing the Red Cross today in its service to those in crisis.

That flag is now being used to terrify whole communities,

rather than a flag of hope for those who are vulnerable.

We’re better than this, aren’t we?

The Mirror thinks that we are.

But, are we? The truth is this is actually happening.

In our worship we bring scripture to life. These are the scriptures of a people who knew what it was like to be hated and persecuted and who also knew what it was like to persecute and exclude others.

Our scriptures know that pride has always driven people to trample on others, and they recognise that “the beginning of pride is the departure from the Lord.”

When we exalt ourselves — our nation, our people, our tribe, our selves — we turn away from God and the truth that God is the beginning of all creation, and that all are fearfully and wonderfully made. All people that on earth do dwell.

Here’s what we believe:

That God has cast down the thrones of rulers, and will continue to do so — seating the lowly in their place.

That God has plucked up the nations, and will continue to do so.

Pride never stands forever. How could it?

Nationalism is pride dressed in flags. It flatters us into believing we are better, more deserving, more entitled. But God’s word says plainly that pride is not for us.

The Letter to the Hebrews points us another way:

“Keep on loving one another as brothers and sisters.

Do not forget to show hospitality to strangers,

for by doing so some have entertained angels without knowing it.

Continue to remember those in prison

as if you were together with them,

and those who are mistreated

as if you yourselves were suffering.”

In a world where strangers are called an invasion, scripture calls them angels.

In a world that says, “Protect our own,” scripture says, “Remember them as if you were in their place.”

The Christian life is not built on pride and self-protection,

but on hospitality and solidarity.

And here’s where patriotism comes in. Because love of country can go one of two ways.

Patriotism becomes caring for our neck of the woods —

the place of our responsibility.

It means humbly rooting ourselves, down to earth.

The only pride we claim is in the small, humble place God has given us to inhabit.

Patriotism is committed to the here and now:

faithful at home, in our house,

on our street, in our village.

This is where charity begins. At home.

Where we grow generous and hospitable.

Charity is sheer grace —

open-handed and open-hearted.

And so, rooted patriotism, shaped by grace,

becomes the ground of our being.

The place of self-giving.

Never taking what is not ours.

Never overreaching ourselves.

But living for the common good.

Building common-wealth.

Isn’t this what Jesus described at the banquet?

He watched guests scrambling for the best seats,

the ancient equivalent of climbing the ladder,

seeking preferment, gaining the place of honour.

Jesus told them not to do that, but instead, to take the lowest place,

which as we know is the place alongside the least and the last,

the very people called First in the kingdom of God.

He said, “Let God honour you.”

“All who exalt themselves will be humbled, and those who humble themselves will be exalted.”

We have a choice. Two ways of living:

Pride says: put the nation first, protect ourselves, keep others out.

The Gospel says: pride collapses, hospitality stands forever.

Pride says: climb higher, sit at the best table, make yourself big.

The Gospel says: take the lowest seat; humble yourself; open the door to those who cannot repay.

“When you give a banquet, invite the poor, the crippled, the lame, the blind … because they cannot repay you.”

Yes, nationalism plays on fear.

And people are anxious, insecure, uncertain.

But the Christian answer to fear is not pride or exclusion.

It is humility, and hospitality, and trust in God.

Every time we come to this table – the Lord’s table – we are reminded of who we are.

Christ welcomes us when we cannot repay.

Christ feeds us as honoured guests when we bring nothing but our need.

This is our story. This is our identity.

When the flag of St George is used to frighten and exclude, we remember who George really was.

He was a foreigner, raised in Palestine,

who gave his life as a witness to Christ.

His flag does not belong to those who wave it in pride.

It belongs to Christ, whose cross humbles the proud and welcomes the stranger.

The flag of St George belongs to all those who pride themselves on living under the banner of the cross – the cross that topples thrones, exalts the lowly, and sets a table where all are welcome.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(757x361:759x363)/White-Lotus-cast-032125-106646e7d7c4489e8f7fcc2715e3927e.jpg)