I am grateful to Justin Lewis-Anthony’s scepticism about leadership. The same day that America was going to the polls to elect Donald Trump I was exploring leadership in ministry with friends and colleagues in the Diocese of Chester including Helen Scarisbrick and Jenny Bridgman. Lewis-Anthony suggests that the leadership bandwagon started rolling in the early 90’s (he blames George Carey), and since then leadership programmes in the church have been proliferating. The Diocese of Chester was quick onto the bandwagon and I was involved in one of their first courses. (I don’t understand why we haven’t given as much attention to other ships which have a more legitimate claim to be part of the fleet – we never hear of friendship, fellowship or companionship training programmes do we, even though there is more theological justification for them?)

Where do our ideas of leadership come from, and why are we so bothered about leadership anyway?

Justin Lewis-Anthony’s book has the clever title You are the Messiah and I Should Know: Why Leadership is a Myth (and Probably a Heresy). He traces our thinking about leadership to the double headed Emersonian “ur-myth” of “the frontier” and “the American Adam”. For Lewis-Anthony “there is a layer of mythology which is omnipresent, omnipotent and omni-transparent, pervading and influencing every part of our understanding of the world. Our knowledge of leadership comes from believing in and living under the power of the myth of leadership”.

There is a reminder here that we can’t escape mythology in ideology. Drawing on the work of Levi-Strauss, Lewis-Anthony reminds us that ideology develop in an unconscious process shaped by the stories which we tell ourselves. He quotes Kelton Cobb (p.99):

Our myths feed us our scripts. We imitate the quests and struggles of the dominant figures in the myths and rehearse our lives informed by mythic plots. We awaken to a set of sacred stories, and then proceed to apprehend the world and express ourselves in terms of these stories. They shape us secretly at a formative age and remain with us, informing the ongoing narrative constructions of our experience. They teach us to perceive the world as we order our outlooks and choices in terms of their patterns and plots.

In other words, we are caught in a bubble – a bind. Once the myth making took place round the camp-fire. Since the 1950’s it’s been on-screen through film making. One nation has dominated the film industry, and consequently the unconscious formation of our ideology. For a long time we have been subjected to the only films available which have relentlessly had the same story to tell. They have fed us our scripts.

Lewis-Anthony quotes German film maker, Wim Wenders: “No other country in the world has sold itself so much and sent its images, its self-image, with such power into every corner of the world. For 70 or 80 years, since the existence o cinema, American films – or better, this ONE American film has been preaching the dream … of the Promised Land.” (p.75).

The frontier is not about place, but about defining experience. It is to the frontier that the American intellect, according to Turner, owes its striking characteristics. “That coarseness and strength combined with acuteness and inquisitiveness; that practical, inventive turn of mind, quick to find expedients; that masterful grasp of material things, lacking in the artistic but powerful to effect great ends; that restless nervous energy; that dominant individualism, working for good and for evil, and withal that buoyancy and exuberance which comes with freedom – these are the traits of the frontier.” (p.81).

The American Adam myth breeds the individualism that Turner talks about and which is such a modern phenomenon. The frontier depend the sense of individualism to the extent that Americans told themselves, according to Billington, that “every man was a self dependent individual, fully capable of caring for himself without the aid of society.” (p.93).

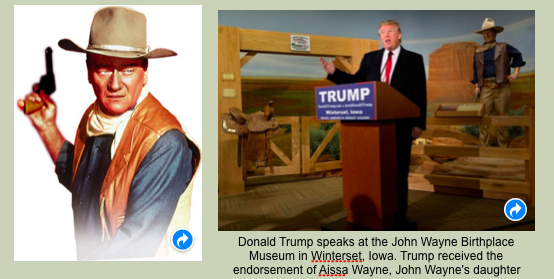

The journey to the frontier is essentially westwards. The journey spawned a genre of film which took over our screens, the “Western”. The western myths of the Western have shaped a leadership that is essentially masculine and white. The films show how the west was won and defended and how the wild was tamed and controlled. Typically the hero is a man “in the middle, between civilisation and savagery”. Lawrence and Jewett describe the Myth: “A community in harmonious paradise is threatened by evil: normal institutions fail to contend with this threat; a selfless superhero emerges to renounce temptations and carry out the redemptive task: aided by fate, his decisive victory restores the community to its paradise condition: the superhero then tends to recede into obscurity.” (p.210).

The American Adam is a man, and a man with a gun. Lewis-Anthony is quite right to point out that in carrying out the redemptive task, the American Adam becomes the American Cain. But it is with the status of hero and leader that this American Cain is expelled, rather than with a curse.

For Lewis-Anthony any leadership based on this Myth is fundamentally violent, and therefore wrong. “Under the American mono myth of redemptive violence, to be a leader/hero means to be prepared to use violence. To be a disciple/follower means to accept, in turn, an invitation to use and be thrilled by violence.” (p.213). Leadership in our society is “fatally flawed by its roots in violence, the will to power and destruction”.

Tom Wright asks the question about “what any of this has to do with something most Americans also believe, that the God of ultimate justice and truth was fully and finally revealed in the crucified Jesus of Nazareth, who taught people to love their enemies, and warned that those who take the sword will perish by the sword”. Lewis-Anthony continues: “Wright reminds those within the church, the ‘religious admirers of leadership’ that there is a basic problem in this admiration of North American society. With its roots in the mythic use of violence by the outsider, the extra-societal Adam, what can we find in the scriptural tradition to counteract, or set aside, this cult of violence? Surely we can find some ways in which the crucified Jesus of Nazareth rescues leadership from both Marduk and John Wayne.”(p.213).

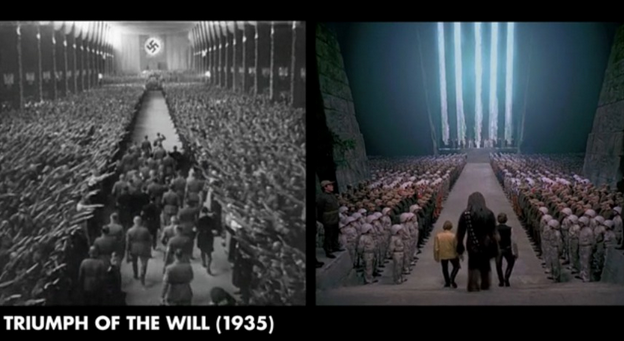

Why are we bothered about leadership? It matters to those who are the victims of leadership violence. It matters to those of us whose minds have been made up by a myth of leadership. It matters to those who are excluded by such a myth – anyone who is not a white, male, rooting’ tooting’ son of a gun. It matters to God’s mission. The Washington Free Beacon has put these two images together, a Nazi rally – which inspired a scene in Star Wars. It all looks frighteningly ecclesiastical, except there’s more people.