a sermon for Easter 3C for St John’s, Weston in Runcorn.

Hallo.

‘Allo, ‘allo.

One of the running gags of TV sitcom ‘Allo, ‘Allo! was the line, delivered in a French accent, “I will say this only once …….”, which was said over and over again, in a comedy called “Allo, allo”.

And we can perhaps imagine the market trader saying, “I’m not going to give you this once, I’m not even going to give you this twice, I’m going to give you this three times.”

That is what we get in today’s readings. We get it three times.

In the gospel, Jesus gives it to Peter three times. “Do you love me?” “You know I do.”

Three times, to correspond with the number of times Peter denied Christ before the cock crew.

Three times to emphasise that Jesus had got over that, that Peter was forgiven.

Three times to underline Peter’s particular pastoral responsibility

I wonder what he says to each of us, this Jesus risen from the dead. What his call is. “Mary, do you love me?” “You know I do.” “Then feed my lambs, teach my people, help them find their freedom.”

It’s not just once that Luke gives us the story of Saul’s conversion. It’s not just twice. It’s three times.

Why?

First of all, I presume it was because he thought this is a story worth telling.

And I presume that it was Luke’s intention that this story should capture the imagination of the church, and help us in our own journeys and our own transformations and conversions.

It’s worth remembering also that it’s not just one, it’s not just twice, but it’s three times that Luke tells us how brutal and callous Saul was towards the followers of the Way.

- In chapter 7, Luke tells us how Saul was involved in stoning of Stephen to death. He may only have been holding the coats, but Luke does say that Saul “approved of their killing him.” He was not a nice man.

- In chapter 8, Luke reports that “Saul began to destroy the church. Going from house to house, he dragged off both men and women and put them in prison.” What was wrong with the man?

- Here in chapter 9, he goes and gets letters from the high priest to authorise him to arrest those who followed Jesus’ Way, and imprison them in Jerusalem. This is a truly frightening man.

What on earth was Jesus doing with Saul?

This is a story of conversion told three times, intended to capture our imagination.

I want to look at this in not just one way, not even just in two ways, but in three.

I want to look at the idea of “going out of our way” (in the sense of waywardness), “mending our ways” and “finding our way”.

And I want to refer not just to one person, Saul, nor even to just two people, but three. I refer to Saul, to the prodigal and to ourselves as the people this story is intended to inspire and transform.

Firstly, Saul.

Saul went out of his way to find the followers of the Way.

It comes across as an obsession.

There are two places named. There’s Jerusalem and there’s Damascus. It’s hardly Runcorn to Liverpool in 20 minutes, so long as there are no lane closures on the bridge. This is 135 miles away, across rivers and mountains, on horseback – perhaps 4 or 5 days away.

Then, lo, Jesus meets him, risen from the tomb.

Lovingly he greets him.

“Who are you?” Saul asks.

“I am Jesus whom you are persecuting.”

And he said to Saul, “Now get up and go into the city, and you will be told what to do.”

And Saul had to be led the rest of the way by hand, and then he was told his way forward.

And what a long way he went.

Luke emphasises all the places Paul went, by road, overseas, through storms carrying Jesus’ to all the nations.

The way was found for Saul, and the way was followed by the convert all the way, all the miles, through trial, suffering, all the way to his death.

Saul’s way, Paul’s way, reminds us of the ways of the prodigal son.

His way was to get his inheritance and run for the time of his life.

Until his luck runs out, and he sees the error of his ways.

The father’s way is to tuck his skirt into his belt and run out to embrace the son he thought he had lost.

Lovingly he greets him, in such an outrageous way that the elder brother protests.

“This isn’t the way.

This isn’t the way to deal with someone who stripped you of half of your money, and who let down the family business.”

And the father says “This is the only way.

The only way to share your father’s pleasure is to forgive your brother. That is the only way. That is my way.”

What about ourselves?

What are our ways? Are they his ways?

Our waywardness may not be as dramatic as Saul’s, or the murderer who becomes a preacher, or the prodigal’s.

Or as awful as Peter’s, who when he realised what he had done just broke down and wept.

Waywardness is part of our reality which is realised in our worship. We confess the ways in which, whether in thought or in deed, we have sinned against our brothers and sisters, and sinned against God.

We ask for God to help us to mend our ways.

We let Jesus lovingly greet us, lead us, his way, so that we may “do justly, love mercy, and walk humbly with you our God.”

That is the way God wants us.

He wants us to walk with him. He wants us to be yoked to him, on the way and all the way. This is the way of life.

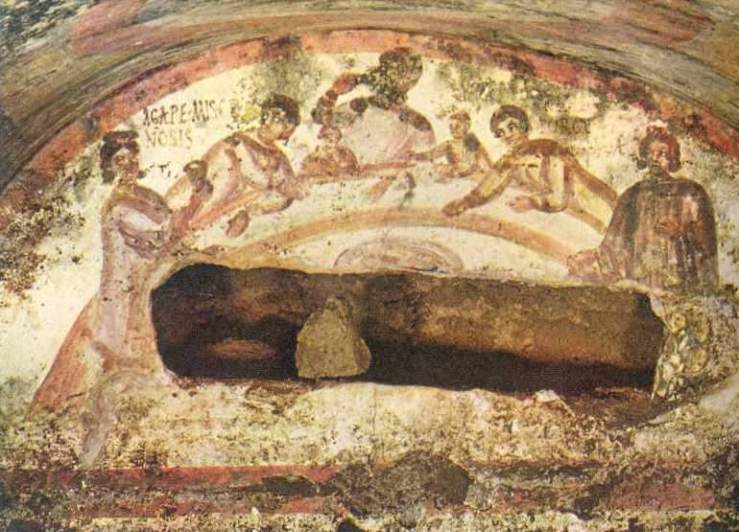

Before Jesus’s followers became known as Christians, they were known as followers of the WAY. The followers of the WAY were known because they had a way of life.

And that way of life is spelled out not just once, not just twice, but three times, by both Jesus and Luke in today’s readings.

Through both Peter and Saul Jesus experienced betrayal and persecution.

To both he showed forgiveness.

For both he gave them a way to go, a direction.

For both there is the prediction of suffering, but for them that was another aspect of walking with Jesus and following his way.

Ourselves, we help each other on our way at the end of our liturgy.

Go in peace, to love and serve the Lord. “In the peace of Christ, we go”.

We don’t simply get on our way.

We commit ourselves to his way, to keep in step with Jesus, loving mercy, and walking humbly with our God as we meet other Sauls, Peters, Sharons and Janets.

What is our way with them?