Dead Heat

dead heat

short head

neck

tied

collared

loose head

tied down

tied up

noosed

tight head

throttled

red

unbutton

untie

the breeze

cool down

breath

tie break

replay

serve

a ministry scrapbook

Dead Heat

dead heat

short head

neck

tied

collared

loose head

tied down

tied up

noosed

tight head

throttled

red

unbutton

untie

the breeze

cool down

breath

tie break

replay

serve

The Feast of Epiphany – when wise ones followed a star, seeing in it the shape of things to come.

The Feast of Epiphany – when wise ones followed a star, seeing in it the shape of things to come.

Poet Mary Karr stitches crucifixion and resurrection to a star (not her words) in a poem called Descending Theology: The Resurrection. I wonder if it is that same star, and I wonder whether the wise ones saw the shape of things to come in the star they followed.

I have stitched Mary Karr’s poem to a particular image of the star of Bethlehem. It is particularly three dimensional, with a reach not just from east to west, but in all directions – to all the nations. (In fact, it has 26 points – that makes a full alphabet for me.)

The poem:

From the star points of his pinned extremities,

cold inched in – the black ice and squid ink –

till the hung flesh was empty.

Lonely even in that void even for pain,

he missed his splintered feet,

the human stare buried in his face.

He ached for two hands made of meat

he could reach to the end of.

In the corpse’s core, the stone fist

of his heart began to bang

on the stiff chest’s door, and breath spilled

back into that battered shape. Nowit’s your limbs he comes to fill, as warm water

shatters at birth, rivering every way.

If you liked this poem you might also like Descending Theology: The Nativity, also by Mary Karr. There’s an interview with Mary Karr by Krista Tippett here. Here’s how to get instructions to make a Moravian star (as pictured).

An old woman grabs

hold of your sleeve

and tags along.

She wants a fifty paise coin.

She says she will take you

to the horseshoe shrine.

You’ve seen it already.

She hobbles along anyway

and tightens her grip on your shirt.

She won’t let you go.

You know how old women are.

They stick to you like a burr.

You turn around and face her

with an air of finality.

You want to end the farce.

When you hear her say,

‘What else can an old woman do

on hills as wretched as these?’

You look right at the sky.

Clear through the bullet holes

she has for her eyes.

And as you look on

the cracks that begin around her eyes

spread beyond her skin.

And the hills crack.

And the temples crack.

And the sky falls

With a plateglass clatter

around the shatterproof crone

who stands alone.

And you are reduced

to such much small change

in her hand.

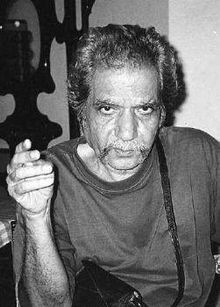

Arun Kolatkar (1932-2004)

This poem describes a fairly typical experience. The reader stands in the shoes of someone accosted in the street by a beggar desperate for money for something to eat. The reader knows what it’s like, to be stuck to “like a burr”. What we often forget, because we want to look past them as if they weren’t there, is that, for the desperate too, it’s part of their everyday, to latch on to others in the hope of charity. The tendency for the accosted is to shake off the attention. The norm for the beggar is to be shaken off.

But, in this poem, there is a notable turn towards compassion. The speaker looks “clear through the bullet holes she has for her eyes”. “You” look through and past her, but as you do so what you look at begins to shatter, and it’s only the “shatterproof crone who stands alone”. Is it then that the bullet hole eyes take on their significance? Is it at this point you recognise her wounds, the battles she may have fought and lost? Is it at this point that you realise what has become of her, and what has become of you in the hands of poverty – that “you are reduced to so much small change in her hand”?

There is such pathos in that last line. There is such small change in small change for a life that should be demanding huge change.

Ox-faced Luke,

Ox-faced Luke,

his gospel yoked

to that load bearing

beast of burden

ploughing on

through life’s muddied field

Ox-bowed Luke,

his gospel bulging

muscle of sacrifice

for the lost, the poor

and stranger still

their inheritance of earth

Luke, author of the third gospel, is often symbolised by a winged ox, one of the “four living creatures” of Ezekiel 1 (and Revelation 4). The ox represents domesticated animals. Symbols for the other evangelists are: (m)an(gel) for Matthew, lion for Mark and eagle for John.

My poetweet this morning responds to a reading of Genesis 3

It’s also the serpent

that opens the eyes of the blind.

And when they saw they sewed,

dressing their nakedness,

hiding their very selves

behind blinds of honesty

from one another,

from God, forever,

till another one with love

opens the eyes of the blind. #Genesis3 #cLectio

Since the dawn of time we have been wanting to help one another to see. “Now, can you see?”, we ask. “Why can’t you see?”, we accuse. I am really grateful for those who have opened my own eyes, for those who have coloured my life with love, those who have helped me to be more open and more confident. I am not so grateful for those who have been more serpentine, those who have insinuated shame into my life.

How can I help others to see? What if I am not careful in the way that I am? What if all I did was bring shame and destroy self-confidence? What if I am serpent like in my feedback and suggestion? What if all I achieved was to force people back into their shell? What if I poisoned their view of the world and themselves?

The serpent said to the woman, ‘You will not die; for God knows that when you eat of it your eyes will be opened, and you will be like God, knowing good and evil.’ So when the woman saw [through the eyes of the serpent] that the tree was good for food, and that it was a delight for the eyes, and that the tree was to be desired to make one wise, she took of its fruit and ate. Genesis 3

How can I help others to see unless someone with love opens my eyes? Until then, I am a blind guide, even blind to the damage I do to the eyes of others.

Every morning I, David, pray with Jews,

my brothers, my sisters. Their scripture

fallen into my hands, fills my mind,

names me. I take their prayers,

the longing of their psalms,

I hear their pain, share their dreams,

my amen I join to theirs.

And I regret every morning

I can’t pray with more distant relatives,

my brothers, my sisters, children of Hagar.

A step too far. What are their longings,

what are their dreams?

I pray, that as I pray, they pray,

with me, for me, amen.

The photo is by mrehan, found at https://www.flickr.com/photos/mrehan00/3455167464

The path of the righteous is like the light of dawn

which shines brighter and brighter until full day. Proverbs 4:18

Who knows where first steps lead?

We feel our way through death’s vale,

beyond the pale to dark corners,

blind alleys, a way hardly taken,

through dark nights of the soul.

This is the path of the righteous,

the path of Missio Dei,

the path of light to dawn.

If you had to choose a poem for Earth Day what would it be? From my limited collection of poetry I have chosen Shoulders by Naomi Shihab Nye. It reminded me of Atlas and his burden – I share the popular misconception that he shoulders the earth (rather than the celestial spheres). Naomi Shihab Nye shoulders hope in her poetry. She says that her poems often begin with the voices of her neighbours, “always inventive and surprising”.

If you had to choose a poem for Earth Day what would it be? From my limited collection of poetry I have chosen Shoulders by Naomi Shihab Nye. It reminded me of Atlas and his burden – I share the popular misconception that he shoulders the earth (rather than the celestial spheres). Naomi Shihab Nye shoulders hope in her poetry. She says that her poems often begin with the voices of her neighbours, “always inventive and surprising”.

Shoulders

A man crosses the street in rain,

stepping gently, looking two times north and south,

because his son is asleep on his shoulder.

No car must splash him.

no car drive too near to his shadow.

This man carries the world’s most sensitive cargo

but he’s not marked.

Nowhere does his jacket say FRAGILE,

HANDLE WITH CARE.

His ear fills up with breathing.

He hears the hum of a boy’s dream deep inside him.

We’re not going to be able

to live in this world

if we’re not willing to do what he’s doing

with one another.

The road will only be wide.

The rain will never stop falling.

this poem is from Red Suitcase

A poor life this, if full of care,

A poor life this, if full of care,

We have no time to stand and stare.

These are the closing lines of W H Davies’s so simple poem, Leisure.

I bet I’m not the only one to be brought up sharp by this. Could this be a Lenten discipline: to take time?

Mary Oliver’s simple lines in Praying might help us to take time in the everyday – just to wonder and wander in prayer. Prayer doesn’t have to be difficult.

It doesn’t have to be

the blue iris, it could be

weeds in a vacant lot, or a few

small stones; just

pay attention, then patch

a few words together and don’t try

to make them elaborate, this isn’t

a contest but the doorway

into thanks, and a silence in which

another voice may speak.

Photo credit: Vilseskogen

Waking in the middle of the night,

say, midway between lying and rising,

just then, is not always curse and cue

for raking old worries to no effect.

just sometimes we awake with a blessing,

precious memories shine our consciousness:

not one, but two lights beam in darkness,

a colon before rest.

where do they come from? they travel far

but arrive fresh. they head straight for me

because only I will know the pair they are.

they come for me, a blessing, a colon before rest.

both were recalls of what was barely

registered at the time of their birth.

one a scholar defining remembrance of Him:

the other, of trouble taken to meet

a paedophile prisoner released

from his sentence. the one the very point

of the other, remembering a man lost

in the darkness of our collective sleep.

After the colon comes the sense, the blessing.

There are some things only we will know,

only alight when they come to see us,

treasure to take us to rest of night.