My eyes were turned by the simplicity of Psalm 123, the psalm appointed for the 6th Sunday after Trinity (year B), prompting this brief exploration of how we pray.

Psalm 123

To you I lift up my eyes,

to you that are enthroned in the heavens.

As the eyes of the servants look to the hand of their master,

or the eyes of a maid to the hand of her mistress,

So our eyes wait upon the Lord our God,

until he have mercy upon us.

Have mercy upon us, O Lord, have mercy upon us,

for we have had more than enough of contempt.

Our soul has had more than enough of the scorn of the arrogant,

and of the contempt of the proud.

July 7th 2024

Can you smoke while you pray? No. Can you pray while you smoke? Of course you can. So goes one of the old jokes about prayer.

How do we pray? I googled “why we pray with our eyes closed”. The answer from Christian Stack Exchange: “For many, prayer is a private matter, an intercession between a person and another higher power. Closing your eyes as you do it is a way to block out distractions and focus on the conversation. Instead of using your eyes to communicate with others, you shut them and turn your thoughts inward.”

The psalm appointed for our worship today (Psalm 123) has been described as a “primer on prayer” (Richard Clifford) and as “one of the loveliest prayers in all of scripture, simple and direct, trusting and confident, spoken out of need and in much hope”. (Bellinger and Brueggemann)

The eyes of the prayer are very much open – and the prayer is very much a public matter.

How do we pray? Poet Naomi Shihab Nye explores Different Ways to Pray:

There was the method of kneeling,

a fine method, if you lived in a country

where stones were smooth.

The women dreamed wistfully of bleached courtyards,

hidden corners where knee fit rock.

Their prayers were weathered rib bones,

small calcium words uttered in sequence,

as if this shedding of syllables could somehow

fuse them to the sky.

There were the men who had been shepherds so long

they walked like sheep.

Under the olive trees, they raised their arms –

Hear us! We have pain on earth!

We have so much pain there is no place to store it!

But the olives bobbed peacefully

in fragrant buckets of vinegar and thyme.

At night the men ate heartily, flat bread and white cheese,

and were happy in spite of the pain,

because there was also happiness.

Some prized the pilgrimage,

wrapping themselves in new white linen

to ride buses across miles of vacant sand.

When they arrived at Mecca

they would circle the holy places,

on foot, many times,

they would bend to kiss the earth

and return, their lean faces housing mystery.

While for certain cousins and grandmothers

the pilgrimage occurred daily,

lugging water from the spring

or balancing the baskets of grapes.

These were the ones present at births,

humming quietly to perspiring mothers.

The ones stitching intricate needlework into children’s dresses,

forgetting how easily children soil clothes.

There were those who didn’t care about praying.

The young ones. The ones who had been to America.

They told the old ones, you are wasting your time.

Time? – the old ones rayed for the young ones.

They prayed for Allah to mend their brains,

for the twig, the round moon,

to speak suddenly in a commanding tone.

And occasionally there would be one

who did none of this,

the old man Fowzi, for example, Fowzi the fool,

who beat everyone at dominoes,

insisted he spoke with God as he spoke with goats,

and was famous for his laugh.

How do we pray? As Jesus taught us so we pray. They’re the words that launch our prayer – “Our Father ……” But surely we want to join Jesus as he prayed. The book of Psalms was his prayer book as it is for all Jews as well as ourselves. The prayers of the Psalms came readily to Jesus’ lips, as we know from the time he was crucified when he directly used the words from Psalm 22. “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me” which, incidentally is a cry of trust, not a cry of abandonment. That prayer goes on:”All who see me mock at me, they make mouths at me, they shake their heads …… Dogs are all around me; a company of evildoers encircles me …… they divide my clothes among themselves and for my clothing they cast lots. But you, O Lord, be not far away! O my help, come quickly to my aid! Deliver my soul from the sword, my life from the power of the dog! Save me from the mouth of the lion!” The psalms and the tradition behind them is where Jesus and his fellow Jews got their prayers from.

Psalm 123 is one of a collection of psalms of ascent – prayer-songs of pilgrims on their way up to festivals in Jerusalem. It’s a personal prayer that becomes a shared prayer. It starts with “my eyes”. “To you I lift up my eyes” which becomes the eyes of the whole pilgrim community. Not “my eyes”, but “our eyes”. This is the prayer of a people matching stride for stride on their way to Jerusalem. Stride for stride, shoulder to shoulder – their eyes lifted to the one “enthroned in heaven, as the eyes of servants look to the hand of their master, or as the eyes of a maid to the hand of her mistress”.

Those of you who have dogs will know that look – as they wait for us to recognise their need, whether that is food, water or a walk. So the eyes of the pilgrims “wait”. They wait “until he have mercy on us”.

This is the manner of the prayer of the pilgrim community – the community who believes in God’s mercy and the people promised God’s blessing by Jesus: those who are poor, those poor in spirit, who mourn, who are meek, who hunger and thirst for righteousness, the merciful, the pure in heart, the peacemakers, the persecuted, the ones reviled and scorned – the “salt of the earth” (Matthew 5:1-13)

This is the prayer of those, who in their own words “have had more than enough”. They’ve had more than enough of contempt, more than enough of the scorn of the arrogant, of the contempt of the proud.

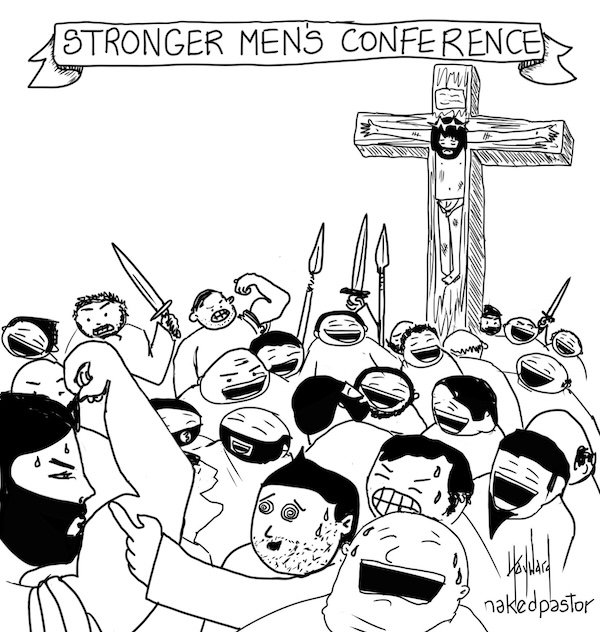

This is how we pray if we join Jesus – himself scorned by his own village and by the powers that be. We join Jesus as he joins others who have had enough, who have had enough of contempt, who have had enough of the scorn of the arrogant and of the contempt of the proud. The arrogant and the proud never look up. They don’t walk as part of the pilgrim community – because they don’t lift up their eyes to the one enthroned in the heavens. Their eyes look down. They look down their noses at the poor, the refugee, the unfit, the least, the lost and all those Jesus promises God’s blessing – the meek, the merciful, the persecuted, the scorned.

I don’t know about you but I’ve had more than enough. I’ve had more than enough of the scorn of the arrogant, I’ve had more than enough of the contempt of the proud. I’m ready to walk with them, stride for stride, shoulder to shoulder – our eyes looking up in hope and expectation to the one who answers our call for mercy, love and a new earth.

When we pray we lift up our eyes. Because of the hope that is in us, we refuse to be be downcast, with eyes cast down, self-defeated. We refuse to look down our noses – we defy the gaze of the proud who admire themselves and look down.

We know the words of “we’ve had enough”. We’ve got the music of the psalms to articulate our prayer. Shall we answer the call to prayer, to join the prayer of Jesus who only joins the prayer of the scorned and those who seek mercy?

Are we going to join Fowzi in his prayer? Are we going to join his laugh? Remember, he’s the fool. Or, rather, he’s the one the proud call foolish. Like us, he’s had enough. He has had enough of the scorn of the arrogant. Shall we follow his eyes as he lifts them to the one enthroned in the heavens, fixed in his search for help and mercy – as the eyes of the servants look to the hand of their master, or the eyes of a maid to the hand of her mistress?

Note: Naomi Shihab Nye’s poem Different Ways to Pray is from Words Under Words: Selected Poems published in 1995.