This is what I emerged with by way of a sermon for Trinity 3A. The gospel from Matthew 10:24-39 was a tricky one. The sparrows caught my eye when I was preparing. So often in his teaching Jesus picks up on what is seemingly worthless and what usually goes unnoticed by others. I wanted us to explore this in relation to Jesus’s mission and the way disciples join his mission by taking up the cross. My exploration took me to the heart of brokenness and all that is wrong in the world. The text of the gospel is at the foot of this page.

The Sermon:

Has anyone got a penny? Long gone is the penny bazaar. You can’t even spend a penny when you’re desperate, when you’ve got everything crossed. A penny for your thoughts. You wouldn’t even give me the time of day for a penny. What’s the point of a penny?

The point of a penny is that it is the price of worthlessness. Way back in the day, before even the pound in your pocket was something, Jesus took up worthlessness when he took up the cross.

Are not two sparrows sold for a penny?

I imagine Jesus at the market, casting his eyes around the stalls and finding someone so poor that all they had to sell was pairs of sparrows. Two-a-penny. You could get them anywhere – and who wants them anyway?

Jesus here is talking poverty. His own family was poor. Tradition had it that after the birth of a first born the mother would offer a lamb to the priest as a burnt offering. This was the law, and it applied to both boys and girls. The exception was for those who couldn’t afford a sheep – then it was to be two turtle doves or two pigeons. That is what Mary offered when Jesus was born according to Luke’s gospel (Luke 2:24). They couldn’t afford a sheep.

Are not two sparrows sold for a penny? They’re ridiculously cheep! Put it another way. The cost of sparrows on the open market is nothing, zilch, nada.

Jesus has an eye for the worthless, for what the world doesn’t even bother counting or noticing, and he uses that in his teaching, like in the parable of the mustard seed and the parable of the leaven. He also picks strands of hair. Nobody counts strands of hair unless they’re folically challenged. Even the hairs of your head are counted.

The point of this passage is not about how precious the sparrow is but about the importance to God of every part of creation, particularly those people overlooked by the powers that be. It’s about those who don’t fit in ……. It’s about those who become “lost” in the system, or the gas chamber, or at sea, those who get lost through the carelessness of others. Most particularly, in this passage, it is about “the lost sheep of Israel” – all those lost by the religious leaders who were supposed to be good shepherds loving everyone dear to God, but didn’t. It’s about those who count for nothing in the world.

And it’s about the disciples themselves. Jesus is aware of the cost of discipleship – that the disciples will be humiliated, flogged, imprisoned, betrayed (even by members of their families), even killed. This is what Jesus’ talk about the sparrows and the hair is leading up to – the encouragement to the disciples not to be afraid of the opposition which will want to discredit and reduce them to nothing.

Jesus stands at the heart of poverty and there gives his life. This becomes his mission and the consequences are the same for him as for those who live at the heart of poverty and brokenness: rejection, betrayal, humiliation and even death. This is the mission, (and the consequences), he is preparing the 12 for in this morning’s gospel, and this is the mission he would love us to join.

We can summarise the mission of Jesus (and the mission of God) as taking up the cross.

One of the questions that has bugged me while I was preparing this sermon is what this means for us. What does it mean for us to take up the cross? It sounds like it is a lot easier for us to be part of Jesus’ mission than it was for those first disciples, or for Christians who continue to live with the threat of persecution, humiliation and hatred. By and large, we live in a society where Christianity has been a dominating culture. I suspect that none of us imagine being persecuted, imprisoned or killed for joining Jesus’ mission taking up the cross.

So what does it mean for us to be taking up the cross in Jesus’ mission?

I played with the word “cross”. I discovered that it is “the cross” in our gospel this morning. It is not “your cross”. Reading “your cross” gives rise to the expression “everyone has their cross to bear”, which might not be true, and which might lead some to think that they’ve got enough to bear carrying their own cross that they’re not going to help carry anyone else’s. If it’s “your cross” it becomes your own bubble of trouble – individualised, almost self-centred.

No, Jesus’ mission is to “take up the cross”, and anyone taking up the cross is worthy of him. Ever since God became the God of the Hebrew slaves in Egypt God has been “taking up the cross” – as it were.

So I played with the word cross. I did a word search of my imagination, and I remembered all the crosses marking my homework and the failure they denoted.

I thought about the crossings out we do and was reminded of those who are crossed out for being who they are, for being wrong – the wrong ethnicity, the wrong race, the wrong gender, the wrong sexuality.

Probably because it was the 75th anniversary of the Windrush landing on Thursday, and probably because it was World Refugee Day on Tuesday, and probably because of the sinking of the boat carrying hundreds of refugees and migrants off the west coast of Greece, I thought of crossings – and the bravery, and the desperation and the exploitation of those who make dangerous crossings.

Already I see the wrong (and who says anyone is wrong?), the wronged, the displaced and the misplaced in the cross. And I see that there is not one cross, with one victim (the object of our worship), but that there are so many crosses and so many for whom Jesus dies to live for in this mission to “take up the cross”.

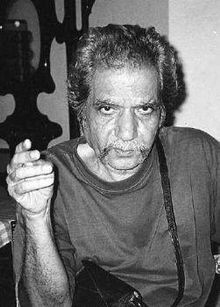

Black theologians are helping us to understand the folly of not using our imaginations when joining Jesus’ mission of taking up the cross. One of them, James Cone, an American, wonders how ever we managed to divorce the cross from the “lynching tree”. James Cone was a black American theologian. He died in 2018.

It didn’t take much imagination for him to link the cross to the lynching tree. In the lynching era, between 1880 and 1940, white Christians lynched nearly 5000 black men and women in a manner with echoes of the Roman crucifixion of Jesus. Cone’s comment on this is that these white Christians didn’t see any irony or contradiction in what they were doing.

Cone writes: “during the course of 2000 years of Christian history, this symbol of salvation [the cross] has been detached from any reference to the ongoing suffering and oppression of human beings – those whom Ignacio Ellacuria, the Salvadoran martyr, called “the crucified peoples of history””.

He continues: “The cross and the lynching tree interpret each other. Both were public spectacles, shameful events, instruments of punishment reserved for the most despised people in society. Any genuine theology and any genuine preaching of the Christian gospel must be measured against the test of the scandal of the cross and the lynching tree.”

I carried on with my wordsearch – my play with the word cross and I remembered that that is how we vote. We put a cross by what we are voting for. And I park that idea – the cross being election and choice. We are free to choose to take up the cross, or we can vote another way.

Then I got my sourdough out of the fridge and got it ready for baking in the oven. Those who have the sourdough baking bug know that you have to score the dough before putting it in the oven. If you don’t score the dough the steam will find the weakest point in the loaf to make its escape. The scoring provides a controlled escape for letting off steam. I score with the cross – and the cross-score becomes the way out, the release, the exodus, as well as the lines along which I would break the bread for sharing with those who are hungry.

And I remember the sign we use for kisses, the cross we choose to show our love for others, and how far we are prepared to go to honour the pledge of our commitment – even to the extent of taking up the cross in our love for them

So, what does it mean to “take up the cross”? Is it something like this?

To choose (elect) to be at the heart of the age-old brokenness of the world with those bearing the burden of that brokenness? Is it to be there with long-suffering love? Is it to be at the broken heart of creation as typified by all Jesus predicted for the 12 (and suffered in his own person) – flogging, imprisonment, humiliation, betrayal?

This is where we’re at, in the midst of brokenness, grief, pain – at the heart of a poverty where life can be so cheap, and when not enough are held dear, where so many are undervalued and so much taken for granted. There is so much wrong. This is where God wants us to be – at the heart of this brokenness and the forefront of his mission.

But just being there is not enough, because those who follow Jesus in taking up the cross are taking up the cross of Jesus which becomes the gateway to resurrection and the new heart of life. Taking up the cross of Jesus is taking up the promise of deliverance – it is trusting that God is at the heart of brokenness, that he is always with us as light and love in the darkness, and that God gives God’s life in the mission he invites us to join. Taking up the cross means taking up the cross in faith, trusting God who sees his people through terrible times of trauma.

So, here we are, as “sheep among wolves”, just like Jesus called those first disciples. He refers to sheep again when he talks about a judgement (Matthew 25:31-46). He divides people into sheep and goats. The sheep are the righteous. They have fed the hungry, given water to the thirsty, welcomed the stranger, clothed the naked, taken care of the sick and visited the prisoner.

The difference between sheep and goats is that goats go their own way, leading the goatherd. The sheep, on the other hand follow the shepherd, just as Jesus encourages his disciples to join him in giving their lives in the brokenness and wrong of the world.

Matthew 10:24-39

“A disciple is not above the teacher, nor a slave above the master. It is enough for the disciple to be like the teacher and the slave like the master. If they have called the master of the house Beelzebul, how much more will they malign those of his household! So have no fear of them, for nothing is covered up that will not be uncovered, and nothing secret that will not become known. What I say to you in the dark, tell in the light, and what you hear whispered, proclaim from the housetops. Do not fear those who kill the body but cannot kill the soul, rather fear him who can destroy both soul and body in hell.

Are not two sparrows sold for a penny? Yet not one of them will fall to the ground unperceived by your Father. And even the hairs of your head are all counted. So do not be afraid, you are of more value than many sparrows.

Everyone therefore who acknowledges me before others, I also will acknowledge before my Father in heaven, but whoever denies me before others, I also will deny before my Father in heaven.

Do not think that I have come to bring peace to the earth, I have not come to bring peace, but a sword.

For I have come to set a man against his father, and a daughter against her mother, and a daughter-in-law against her mother-in-law and one’s foes will be members of one’s own household.

Whoever loves father or mother more than me is not worthy of me, and whoever loves son or daughter more than me is not worthy of me, and whoever does not take up the cross and follow me is not worthy of me. Those who find their life will lose it and those who lose their life for my sake will find it.