Sometimes one sermon leads to another. The focus here is Hebrews 11:29-12:2, very much picking up from last week’s sermon commending those who never give up and never settle for the way things are, always hoping for justice and love. Here we join the author of Hebrews in looking more closely at who these people are because they really are our cheerleaders. The gospel reading is Luke 12:49-56.

This morning I want to bring to your attention the great cloud of witnesses who surround us.

It is such an evocative image that the author of this letter to the Hebrews has brought to the church.

It is a piece of art.

(The authorship of Hebrews has been kept a mystery.

There is a strong case that the author is a woman – perhaps Priscilla, named as a church leader in Paul’s letters.

Her authorship may have been suppressed because she was a woman.

To avoid repeatedly saying “the author” I’ll be using the pronouns, she/her.

I think it’s helpful to picture the hand of the person writing this letter.

It may well be a woman’s hand.)

Last week we heard from her letter the closest the Bible comes to defining faith:

“Faith is confidence in what we hope for and assurance about what we do not see” (Hebrews 11:1).

She then gave us a list of people who lived faithfully in hope and love, never settling for anything less that what God had promised.

She commends them for their faith.

She lists some by name:

Abel, the first of many victims of resentment and murder,

Enoch, the first of “the disappeared” – those who vanish without a trace,

Noah, the first of many victims of flooding and climate change, and

Abraham, the archetypal migrant, forever moving from place to place, a stranger and foreigner wherever he went, refusing to settle for the world as it was, forever following a call into a future he could not yet see.

They’re the patriarchs of faith.

But she goes on to name others, and, in today’s reading (Hebrews 11:29–12:2),

to hold up a whole host of unnamed witnesses.

These, too, are the people she commends for their faith.

The technology she has at her disposal was words, and she uses them like a camera lens – zooming in so we see them vividly.

She populates the crowd. They are not faceless.

She wants us to see them for who they are.

She has given us a series of close-ups of them.

Here they are.

They faced jeers and flogging, even chains and imprisonment.

They were put to death by stoning, they were sawn in two, they were killed by the sword.

They went about in sheepskins and goatskins,

destitute, persecuted and ill-treated,

They wandered the desert and mountains, living in caves and in holes in the ground.

These are the people commended for their faith.

Have a look at them. They won’t mind you taking their photo.

See the man in the torn sheepskin,

and the woman whose wrists still bear rope marks.

See the exile who carries home only in memory

and the young man with a limp and joy in his eyes.

Take those photos to heart. Treasure them.

None of them are ever going to make the front cover of Vogue.

They are the last people anyone would think of.

But this is the kingdom of God we are talking about,

where there is one rule

that the first shall be last, and the last first.

And this is sacred scripture,

the treasure of those who are last, lost and least in the kingdoms of this world,

whose hope is stubborn, resilient, never-say-die,

and will settle for nothing less

than the justice and mercy of God’s kingdom.

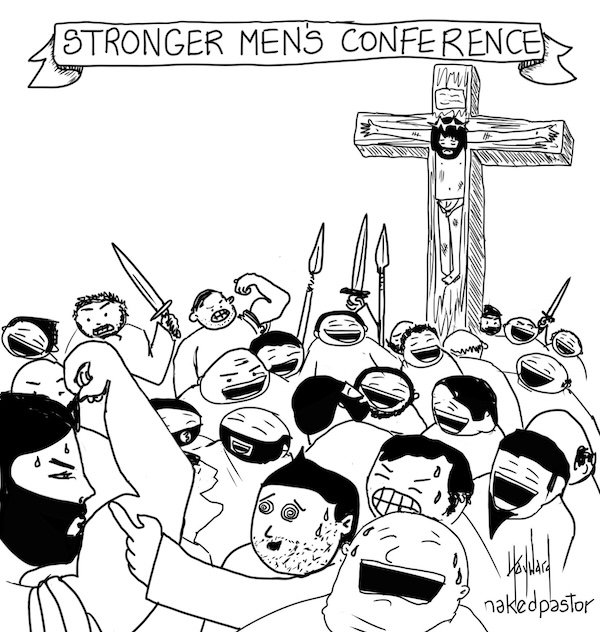

This cloud of witnesses surrounds us:

not a polished gallery of saintly portraits,

but a motley crew — scarred, weathered, unkempt, unruly.

They are our cheerleaders.

Imagine them as the author of Hebrews wants us to.

Imagine each and every one of them cheering you on.

Come on Margaret, Come on Niki.

“Don’t give up”, “Don’t get downhearted”, “Don’t beat yourself up”, “Keep hope alive”.

We look after our grandchildren two days a week.

One of them is soon to be 5, the other is 2.

The days are long and hard.

These days highlight my weaknesses, especially as we all tire towards the end of the day.

Patience wears thin. I can feel mean, and I hate myself for feeling like that.

But there are other times when I see how good I can be and how helpful I can be to them.

I love that, and they love that.

I suspect many parents, grandparents and carers know what I’m talking about, especially in the long summer holidays.

In moments like those, moments of temptation, weakness and vulnerability we need the right voices in our heads and ears.

We need to hear these cheerleaders who’ve come through their trials.

But there are other cheerleaders too, if we can call them that,

The voices of dog whistlers and fearmongers

egging us on in a different race altogether:

the race to be anxious about everything,

to fear the stranger,

to protect our own at the expense of others,

to trade trust for suspicion and love for self-preservation.

They sound persuasive because they speak the language of fear — and fear is loud.

But it is not the language of the kingdom.

Hope is the language of the kingdom.

Mercy is the language of the kingdom.

Love is the language of the kingdom.

The gospel ends with Jesus asking a question, more or less wondering to himself,

“How is it that you do not know how to interpret this present time?” (Luke 12:56)

It may be that we have got it wrong, that we are seeing things the wrong way,

through the wrong eyes.

The author of Hebrews has given us a different picture,

a picture of the last and least who lived for hope, mercy and love.

They’re the eyes through which we need to see the present time,

the mean time that we are called to live through with faith.

They’re the cheerleaders who love us,

who want us to run well the race that is set before us,

who cry out “Don’t give up! Keep hope alive!”

Don’t give in to those who put themselves first.

Don’t give in to those who want to lose you and confuse you.

Don’t give in to those for whom you matter least.

They are the ones who have come last, been least, and got lost,

who were beaten, broken and jeered,

but who persevered, running their race,

and are commended for their faith.

They never gave up, and they don’t want us to either.

They want us to keep running forward

till mercy, justice and love become the rule of the day.

Theirs are the cheers we need to hear.