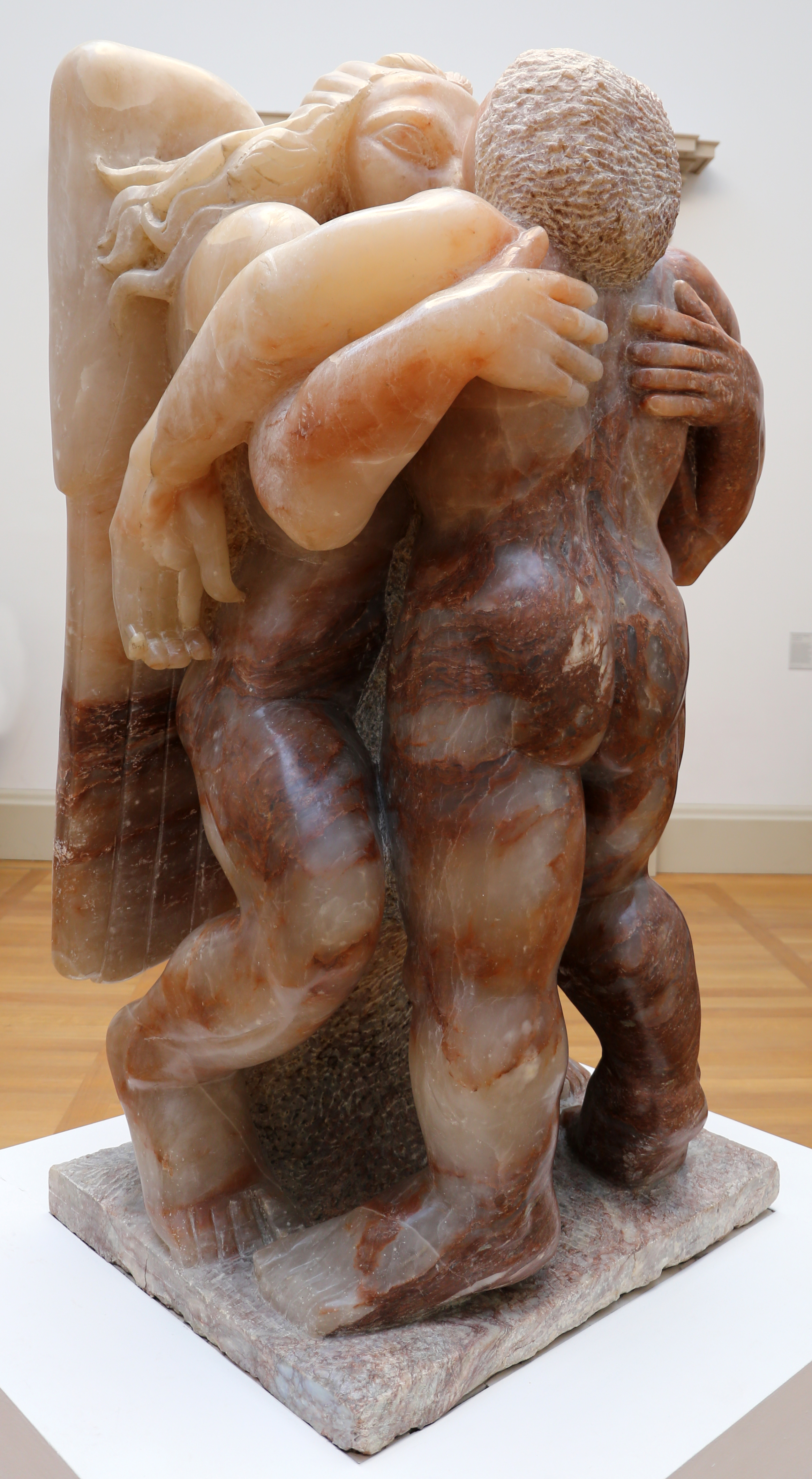

This one’s for all who wrestle in the dark and rise, blessed but limping, inspired by reading Genesis 32:22-31 and Luke 18:1-8 – the Revised Common Lectionary readings for October 19th 2025.

How shall we describe the state of Israel today?

The state of Israel today begins with both our readings —

from Genesis 32, the story of Jacob whose name means twister;

and from Luke 18, the story of the widow struggling for justice.

The state of Israel begins at the end of a night of struggle for the twister,

a night of struggle in which Jacob never discovers

the name of the one he’s wrestling with,

but finds himself called by a new name — Israel.

Israel struggles with God,

and God struggles with Israel.

That is the very meaning of Israel.

If Israel means anything,

it means struggling with God.

Jacob is the first to be called Israel,

and he is called (renamed) that by the one he struggled with

because he “struggled with God and with people”

and withstood the whole night.

It is the calling of Israel to struggle faithfully through the night.

Jacob is the patriarch of Israel —

the patriarch of those who struggle with God and with people,

and who carry on wrestling through long nights and times of darkness

without being overcome,

people like the widow singled out by Jesus —

a victim of some injustice.

In the face of an utterly unjust justice system,

personified by a judge who neither feared God

nor cared what people thought,

she struggled.

For some time she struggled.

She kept coming at that lousy judge.

She wouldn’t let go until he gave in.

Those who struggle through the night,

with God and with people —

those who struggle to see the night through,

for whom the night is very dark,

and for whom there is little daylight,

those who won’t give up whatever the night brings —

they are the ones whose hope is rewarded.

They carry a blessing for all who wrestle with God

and with the wounds people inflict.

It’s the blessing of God

who himself wrestles through the darkness of the world,

who struggles with people and the suffering they cause,

but who, in spite of all that,

wrestles the whole night long.

This is the love that shines in the darkness

to the break of day.

And yet, the night is long.

Not just one night in Jacob’s life,

not just one night in ours,

but the long night of the world —

a night as long as history.

Through that long night we wrestle,

and God wrestles with us.

There are three struggles woven into this story,

and all three belong to Israel:

We struggle with God.

We struggle with people —

and people struggle with us.

And through it all,

God struggles with us.

That’s what it means to be called Israel:

to live the long night of wrestling,

and to trust that, at the end of it,

there will still be blessing.

The struggle with God

Sometimes it’s the long silence of prayer —

when we ask and wait and hear nothing.

Sometimes it’s the ache of loss,

or the questions that faith won’t easily answer.

We wrestle with God when life doesn’t fit the promise,

when love feels hidden,

when blessing comes only after a wound.

But still we hold on.

Faith is not certainty —

faith is the grip that will not let go until morning.

The struggle with people

And we wrestle with people too.

Not just those who hurt or wrong us,

but in all the difficult ways love tests us —

learning to forgive, to be patient,

to stay kind when we’d rather give up,

to bear with one another’s weakness.

People struggle with us too —

our faults, our sharp words, our stubbornness.

We are all part of each other’s wrestling.

These are the struggles that form the fruits of the Spirit —

the quiet strength that grows only in the dark:

patience, gentleness, self-control,

love that endures through the night.

The struggle with ourselves

And maybe there’s a fourth struggle too —

the one Jacob knew best —

the struggle with ourselves.

The fight to face what we’ve twisted,

to tell the truth about who we are,

and to accept the new name that grace gives us.

Before we can meet God face to face,

we have to face ourselves in the dark —

the parts we’d rather not see,

the wounds we’ve caused as well as borne.

Even that struggle can become blessing.

The struggle of God

And through it all, God struggles too —

not against us, but for us.

God wrestles through the night of the world,

bearing our pain,

refusing to give up on us.

The cross itself is the mark of that struggle —

God’s own wound,

the divine limp that still bears the weight of love.

This is the love that shines in the darkness

to the break of day.

Jacob wanted to know the man’s name,

but the man would not tell him.

Maybe that’s the mercy of God —

that we never get to hold the name too tightly.

The namelessness keeps the struggle open.

It reminds us that this wrestling is for everyone,

that God stands with all who struggle through the night —

beyond borders, beyond certainty, beyond control.

It was not for ease that prayer shall be.

The story of Israel is not the story of the untroubled.

The story of Israel is the story of the very troubled —

the story of slavery, exile, persecution,

the horrors of history, the nightmare.

Amos got it right three thousand years ago.

He condemned the complacent,

those who are at ease in Zion.

He said they put off the day of disaster

and bring near a reign of terror.

They are not fit to be called Israel.

They duck the fight and ignore the struggle.

But Jacob did not.

The widow did not.

And the God who wrestles through the night does not.

Jacob’s blessing comes with a wound.

He carries it into the dawn,

every step a reminder of the night he endured

and the God who would not let him go.

Perhaps this is the mark of the blessed —

not the ones who have had an easy time of it,

but the ones who have been wounded and changed.

The ones who know that life is not straightforward,

that faith is not certainty,

and that love costs something real.

Israel limps into the sunrise,

blessed and broken.

And still, the night is long —

as long as history,

as wide as the world.

Still, God wrestles with us,

still struggles with his people,

still bears our wounds,

and still blesses us.

And when the dawn comes —

as surely it will —

the blessing will not erase the limp,

but redeem it.

For the love that shines in the darkness

will shine until the whole world

limps into the light.

Afterthoughts

What might it mean for a people, or for a church, to be known by its limp – to be blessed not in strength but in struggle?

If God still wrestles through the long night of the world, where do you see that struggle – and that love – happening today?