A sermon for the 2nd Sunday of Easter – Year C for two small churches. The gospel for the day is John 20:19-end.

I love preaching that brings Scripture to life—and that brings Scripture back to life.

That’s a line I’m going to repeat each week to remind us that every time we open Scripture together we are bringing it back to life.

This morning we return to John’s Gospel, still caught up in the wonder of that first Easter day (John 20:19-end). It’s a story only he tells.

John himself brings scripture back to life.

Particularly we see the influence of the creation story from the 1st chapter of our scriptures.

We can see that in the way that he tells us the time.

On the evening of that first day of the week.

It’s like last week’s gospel reading which began: Early on the first day of the week, while it was still dark. (John 20:1)

We are still on that first day which was like the first day of creation, when, according to Genesis 1:2, earth was a formless void and darkness covered the face of the deep.

That’s the time in today’s gospel. It was the first day of the week, and it was evening.

In other words, darkness was forming.

Taking our cue from Genesis, John’s readers can expect God’s wonders on this new day of creation.

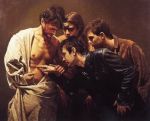

Thomas wasn’t with the disciples when Jesus came on that first day, the day of resurrection.

It was the other disciples who had to let him know that they had seen the Lord.

Thomas told them that he would never believe “unless I see the nail marks in his hands and put my finger where the nails were, and put my hand into his side”.

It is this I suggest we focus on in our worship today.

Thomas is the patron saint of those who are blind because seeing wasn’t enough for him.

He needed to examine Jesus’s wounds by touching them and feeling them.

And the wonderful thing on that second Sunday, the first day of the week following, was that Jesus came and stood among them again and showed Thomas his wounds.

He welcomed his touch. He guided his hand. He let him explore his body.

Thomas is the patron saint of those who struggle to believe what they can’t see—or even what they can.

He shows us that resurrection faith isn’t just about seeing.

Sometimes it’s about touching, questioning and wrestling with God.

Jesus showed Thomas his scars. He wants his disciples to see them.

In the Last Supper, he took a loaf of bread and he broke it.

He wanted them to see his body in the brokenness of the bread.

“Take, this is my body,” he said. (Mark 14:22).

Then he gave them a cup for all of them to drink from.

In that cup he wanted them to see his blood.

“This is my blood of the covenant poured out for many.”

Even before he was wounded he wanted to show his disciples the wounds he was going to suffer.

And in today’s gospel, in one of his resurrection appearances, he invites Thomas to have a look at those wounds – to examine, inspect and see with his hands as well as his eye.

Thomas recognises Jesus through his wounds, just as Jesus wanted him to.

And this is how we come to know Jesus.

Just as Thomas encountered the risen Christ in his wounds, so too we encounter him today in the bread and wine of the Eucharist.

Every Communion we have with Jesus we have this invitation to examine the wounds of Jesus. Every time the bread is broken we are invited to see the brokenness of the body of Christ and to feel that brokenness in our mouths.

Every time we take this cup we are invited to taste the blood of Christ shed for us.

What is it that Jesus showed Thomas?

What did he want his disciples to see?

What does he want us to see when he shows us his wounds, when he invites us to see his body and his blood?

The first things we see are the wounds to his hands and feet where the nails were driven into his body by the hammer blows of empire.

Then, if he turns we see the wounds of the whipping scored into his back for being the scourge of empire and religion.

Then we see the scars on his head where they pressed the crown of thorns and added insult to injury, to press home the point that this “pretender” was nothing.

The rule of the kingdom of God is that the last, the lost and the least come first and those who are first in the kingdoms of this world come last.

The rule of the kingdom of God turns the rules of the world upside down.

In the wounds of Jesus, his disciples see a man who embodies that rule of the kingdom of God. In the brokenness of his body, in the bloodshed, we see a man the religious and political capital tried to reduce to nothing.

The plots against him and his crucifixion were intended to humiliate him and his followers – to make them least, last and lost – GONE for ever.

The problem for them was that the rule of the kingdom of God puts the least, last and lost – those lost and broken by the ways of the world – first.

When Jesus stood among his disciples, first without Thomas, then with him, he was the living proof of the fundamental rule of the kingdom of God.

Here was the humiliated, crucified and killed one.

You can’t get more “least, last and lost” than that.

Here he was, “the first fruits of those who have died”, Christ raised from the dead (1 Corinthians 15:20).

This is what Jesus showed Thomas –

the scars are the living proof of the rule of the kingdom of God.

Jesus stood among them as living proof of the rule he’d always followed,

that puts the last first and the first last.

Here is the one they put last made first.

This is what Thomas saw. This is what he said:

“My Lord, my God” – the rule of the kingdom of God realised in those few words.

“My Lord and my God” – Jesus comes first for Thomas.

So Jesus stands among us still, not with condemnation, but with scars.

What do we see? What difference does it make? Does Jesus come first?

Jesus doesn’t shame Thomas for his questions. He meets him in them.

He doesn’t rush belief. He invites it — gently, patiently, personally.

And he does the same with us.

To all who doubt, who ache, who long to see and touch and know — he says,

“Here I am. Peace be with you.”

He doesn’t hide his wounds. He offers them.

He lets us trace the pain and the mystery of a love that suffers with us and for us.

And in that wounded, risen body, we find our hope.

This morning, he says again:

“This is my body. This is my blood.”

This is how I choose to be known.

Look closely. Taste carefully.

And, if you are among the broken,

do not be afraid.