We’ve stayed up!

We’ve stayed awake

to make this night,

this night above all nights, holy.

And we’ve sung praise to this holy night.

Perhaps for the first time tonight in this church

have we sung congregationally the lovely carol, Cantique de Noel.

Noel is a word from Anglo-Norman French. It means birthday.

So when we sing Noel, we are singing a birthday song to the world –

a new beginning sung into the night.

This holy night we see God

as light, forever a-light in our darkness,

a light in our fears, aloneness and confusion.

Tonight we see night as the time God acts.

God’s creation begins in darkness.

That’s our Genesis.

The Exodus began in the dark.

The resurrection begins “while it was still dark”.

God works the night shift.

Tonight we see God –

the very nature of God,

seen and worshipped

as the smallest,

the most vulnerable of life.

This is how we see God,

in a stable, in the busyness

of a crowd of people, in a state

preoccupied by the presence of enemy power.

We see God in that darkness,

and we begin to love the name of that baby,

Jesus, the one who saves us

by joining our darkness with the lightness of love.

As night follows day, he is with us

in the darkness of hurt and disappointment,

rejection, betrayal, the loss of loved ones,

the anxiety of making ends meet,

in a world of war, and a world in flight –

he is with us, our boy, Emmanuel.

Grace doesn’t come with a sword

to overcome the darkness with a spectacular blow.

Instead God illuminates the darkness

with everlasting companionship.

And in this new light, we see ourselves again

as the very image of God.

This holy night, God appears small,

and that smallness reveals what God is always like.

The manger isn’t camouflage, it is revelation.

The manger is our mirror image.

We are made in the image of God,

not born to be high and mighty, first and foremost,

but born into smallness – humble at heart.

And this is the best possible light,

this night, to see one another.

Even though we are in the dark

God helps us see his work begin in smallness,

even with the least, the last and the lost.

God imagines us all worth visiting,

all worth illuminating, all worth saving.

And perhaps, finally,

this holy night invites us

not only to consider how we see God,

or how we see ourselves,

or how we see one another –

but how God sees us.

God does not look for the impressive,

the sorted, the strong.

God looks with delight

upon those awake in the night,

those keeping watch,

those doing their best to get through.

This is the light God shines upon us:

not a searching light,

not a judging light,

but a warming one.

A light that says,

You are worth visiting.

You are worth staying with.

You are worth saving.

This holy night,

God sees us as beloved.

And that is blessing enough

to carry us back into the dark,

Unafraid.

Good night.

Tag: vulnerability

This Is How It Began – in the middle of winter

Preached on the Fourth Sunday of Advent, this sermon sits with Matthew’s telling of Jesus’ birth at midwinter — when the light is weakest and hope can feel thin. It explores how God chooses to begin again not in tidiness or certainty, but in the mess, risk, and vulnerability of ordinary human lives.

This is how the birth of Jesus the Messiah came about.

These are the words Matthew uses to describe the birth of Jesus.

This is how it happened.

This is how it began.

When I say,

“these are the words Matthew uses,”

what I really mean is,

“this is how we have translated the words Matthew wrote.”

Matthew wrote in Greek,

and the key word in that opening sentence is a Greek word we know very well, the word genesis.

Τοῦ δὲ Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ ἡ γένεσις οὕτως ἦν· μνηστευθείσης γὰρ τῆς μητρὸς αὐτοῦ Μαρίας τῷ Ἰωσήφ, πρὶν ἢ συνελθεῖν αὐτοὺς εὑρέθη ἐν γαστρὶ ἔχουσα ἐκ πνεύματος ἁγίου

Genesis.

Beginning.

Origin.

The start of something that will change everything.

Matthew is not just telling us how a baby was born.

He is taking us back to the very beginning.

Back to the beginning of the world.

Back to the beginning of God’s work with humanity.

Back to what begins with Jesus.

It is no accident that we hear this reading now

— on the shortest day of the year,

at midwinter,

when the light is at its thinnest and the night feels longest.

Because beginnings often come like that.

Quietly. In the dark.

When the ground looks bare and the fields seem empty.

When nothing much appears to be happening at all.

This is when God makes his presence felt.

Matthew takes us back to a beginning that looks very small.

Just as in Genesis, there is a young boy and a young girl.

But they’re not Adam and Eve. They are Joseph and Mary.

Ordinary people with complicated lives.

Adam and Eve walked freely with God.

They had no backstory.

No reputation to protect.

No neighbours to worry about.

But Joseph and Mary live in a world where things are already tangled.

Mary is pledged to be married, but not yet married.

Joseph is a good man, but suddenly faced with a situation that could cost him his standing, his future, his place in the community.

This is not a beginning without consequences.

This is a beginning that arrives already burdened.

And God does not wait for a cleaner moment.

God begins again here — not in freedom, but in constraint;

not in clarity, but in confusion;

not in daylight, but in the deepening darkness.

This is how the birth of Jesus comes about.

Not by sweeping the mess away, but by entering it.

Not by restoring the world to how it once was,

but by beginning something new within the world as it is.

in a teenage love story,

in the vulnerability of these two youngsters.

Both are vulnerable.

Mary is pledged to Joseph but not living with him.

She’s pregnant. People are going to talk.

If she’s not been with Joseph, who has she been with?

She is at risk of being shamed, isolated and abandoned –

a public disgrace.

Joseph is vulnerable too.

He has the reputation of being a righteous man

because he tries to do the right thing.

If he stays with Mary he risks his reputation

(costly to his business and his standing).

If he leaves her she is exposed.

There is no clear path.

And here God begins.

In this mess framed by confusion, risk and fear.

God begins again by stepping into lives that are already complicated

— and trusting them with something holy.

Genesis does not wait for spring.

It begins when the light is weakest

in the midst of winter,

and slowly grows from there.

When God begins here, it is not with explanations.

Matthew tells us that Joseph makes up his mind.

He decided what he will do.

And then God speaks.

Not in public,

not with spectacle,

but in the dark night,

In a dream.

The angel does not tidy the situation.

He does not remove the risk.

He does not promise that everything will be all right.

He says only this:

Do not be afraid to take Mary as your wife.

Do not be afraid to stay.

Do not be afraid to be seen.

Do not be afraid to let your life be changed.

And then Matthew gives the child a name.

Emmanuel.

God with us.

Not God with us when the mess is sorted.

Not God with us when the rumours stop.

Not God with us when life feels safe again.

But God with us, here,

in confusion,

in vulnerability,

in teenage love that chooses faithfulness over self-protection.

When Joseph wakes up,

he does what the angel has told him.

And that is how the story moves forward.

Not through certainty.

Not through control.

But through trust.

And this is the genesis Matthew chose to share with his readers,

how God begins his work

these days that are long with darkness.

He begins with a boy and a girl,

with ordinary people inspired to trust.

Slowly, quietly, faithfully the light begins to grow.

This is how the birth of Jesus comes about.

God begins again –

with us –

in the dark.

NOTE

I make no secret of the fact that I’m greatly helped by AI when preparing sermons. Used well, it doesn’t write sermons for me, but helps me listen more closely — to Scripture, to season, and to the lives of the people I’m preaching among. This sermon is better than it would otherwise have been, and I’m grateful for the help.

Blessing the small, the least, the last and all those suffering empire.

A sermon for Trinity 20A. I focus on Jesus takes a people bruised and battered by empires to a whole new realm. The readings are printed below. They were Isaiah 45:1-7 and Matthew 22:15-22. It was the emperor in each of the readings which first grabbed my attention.

October 22nd 2023

My Bible

These are the writings of a bruised and battered people who have lived through the worst of times.

This is the reading of a bruised and battered people.

This is their literature. They have treasured it. They have handed it on for the sake of other bruised and battered people.

As always our scriptures are brought to us by a troubled people. It is a troubled people, inspired in the Spirit of God who have chosen the scriptures we inherit and hand on. It is a troubled people who have treasured them and bottled them for us because they have been a a very present help in times of trouble.

They are a people who have had all kinds of suffering inflicted upon them by dominating empires, from slavery in the hands of the Egyptian empire, to destruction of their institutions, to exile, persecution and occupation by the Assyrian, Babylonian, Greek and Roman empires. Their imperial domination, at various times, took their labour, their homes, their institutions, their land, their networks, their lives. Our scriptures give us the very best trauma literature and survival resources.

For those dominated by powers which are not their own there is always the question, “how do we get through this?”

This morning’s readings, brought to us by a traumatised people feature two emperors. In the red corner we have Cyrus whose Persian empire survived a mere 7 years in the 6th century BC. He is the golden boy amongst emperors. He shows us that it is possible for those rich in power to enter the kingdom of heaven by allowing God to take his hand (and arms) to dismantle empire and repair its damage. He is called the Lord’s anointed in our reading from Isaiah – provides a happy and short interlude.

In the blue corner we have the unnamed Caesar, the Roman emperor.

The question the unlikely alliance of Herodians and Pharisees ask Jesus is a trick question. The answer Jesus gives isn’t a simple “pay your taxes”. It’s a trick answer. Pay Caesar what is his. What is his? What is rightfully the emperor’s in a land which he has taken from others. It’s a trick question with a trick answer. Underlying both is that harder question of how do we live with this overwhelming, stifling foreign power?

When we read our scriptures we are always bumping into emperors and hearing of the troubles and damage that they bring. That is the context.

I don’t know whether you will agree with this assessment of our own context – that most of us have shared the benefits and privileges of empire, that we might feel uneasy in the aftermath of empire, uncomfortable about what we might have taken from others and unsure about how we begin to repair the damage.

Empire is always our context. They are built all around us. We may be one of their builders. The superpowers operate imperial models. There are global empires like Amazon and Google (and who should they pay taxes to?) There are the media empires and their hidden persuaders with their bots affecting our habits and views. These are large empires. There are other empires operating the other side of the law – the drug cartels with their barons, the warlords, people traffickers, as well as the little empire builders we see around us. Mr Big always brings favours to some and trouble to many. He is always self serving.

This is our context. And this is the context for Jesus’ teaching about a kingdom and way of life so radically different from the ways of empire. Jesus was tempted by the ways of empire – world domination, stunts and political popularity were not going to be his way. He saw the devil in them.

Instead he helped his followers explore a different realm – a realm in which there is no domination and only amazing grace. To these troubled people Jesus offered an alternative vision of hope. He opens up a kingdom in which everything is small and vulnerable rather than mighty and impregnable.

He casts around for images that we will all understand. To what shall I liken the kingdom of heaven? To people so often belittled by empires, to people who can so easily be lost or disappeared, to a people whose lives are hidden and voice unheard he likens the kingdom to things that are hardly noticed and that can so easily disappear. Like the mustard seed, the smallest of all seeds. Like the leaven folded into the loaf. Like the scattering of seed.

He trains our eye on the birds of the air and the lilies of the field and says there is no glory in empire, nothing like the glory of the lilies of the field. To those who have little, he shows what can be done with little – feeding 4000, feeding 5000.

He turns the world’s rule upside down by saying to those used to coming last that the rule of his kingdom is that the last come first and the first come last. He turns the world upside down by putting children central to the kingdom of heaven, the qualification for entry being that we have to become small and just like a child.

We love to remember that the son of God came to us as smaller than a child, a baby. The teaching he shares is his learning to be a child. In John’s gospel, Jesus teaches that we have to be born again, to seize the opportunity of a second chance of being children.

In that gospel Jesus is just a ray of light that shines in overwhelming darkness, the word of God in edgeways. The words that come to mind when we think of God’s kingdom – if we have learned anything from Jesus – is small and vulnerable.

Maybe it is only as I have retired from the church’s institutions and put some distance between myself and the systems and thinking which mimic the ways of empires and powers, that I have seen, as if for the first time, that the kingdom of heaven is only to be understood in things small, hidden and vulnerable, and that the kingdom of heaven is for those who are the last and least chosen in the kingdoms of this world – for the hidden and vulnerable, and for those who are prepared to make themselves small for the sake of the kingdom.

I have noticed this particularly in this year’s successive gospel readings from Matthew.

At the beginning of his gospel Matthew gives us a name for Jesus, Emmanuel. That name means “God with us”. At the end of his gospel he gives us a promise to remember. “I am with you always, to the end of the age.” He shows the battered, bruised and bloodied people the battered, bruised and bloodied face of Jesus – joined with them in their suffering – and he shares Jesus’s blessing of them.

How blessed are you who are poor in spirit – yours is the kingdom of heaven.

How blessed are you who mourn – you will be comforted.

How blessed are you who are meek – the earth will be yours.

How blessed are those of you who hunger and thirst for righteousness. You will be well satisfied.

How blessed are you who are merciful. Mercy will be shown to you as to no other.

How blessed are the pure in heart. You will see God in the smallest and most vulnerable.

How blessed are those of you who are persecuted. Yours is the kingdom of heaven.

This is the blessing of a bruised and battered community. Today we join them in reading their scripture, in their prayer, in their struggles, in their blessing and in the kingdom prepared for them.

Isaiah 45:1-7

Thus says the Lord to his anointed, to Cyrus,

whose right hand I have grasped

to subdue nations before him

and strip kings of their robes,

to open doors before him –

and the gates shall not be closed:

I will go before you

and level the mountains,

I will break in pieces the doors of bronze

and cut through the bars of iron,

I will give you the treasures of darkness

and riches hidden in secret places,

so that you may know that it is I, the Lord,

the God of Israel, who call you by your name.

For the sake of my servant Jacob,

and Israel my chosen,

I call you by your name,

I surname you, though you do not know me.

I am the Lord, and there is no other;

besides me there is no god.

I arm you, though you do not know me,

so that they may know, from the rising of the sun and from the west, that there is none besides me;

I am the Lord, and there is no other.

I form light and create darkness,

I make weal and create woe;

I the Lord do all these things.

Matthew 22:15-22

Then the Pharisees went and plotted to entrap him in what he said. So they sent their disciples to him, along with the Herodians, saying, “Teacher, we know that you are sincere, and teach the way of God in accordance with truth, and show deference to no one; for you do not regard people with partiality. Tell us then, what you think. Is it lawful to pay taxes to the emperor, or not?” But Jesus, aware of their malice, said, “why are you putting me to the test, you hypocrites? Show me the coin used for the tax.” And they brought him a denarius. Then he said to them, “Whose head is this, and whose title?” They answered, “The emperor’s”. Then he said to them, “Give therefore to the emperor the things that are the emperor’s, and to God the things that are God’s.” When they heard this they were amazed, and they left him and went away.

The leadership and ministry of fools (and other outsiders)

The Fool features in much of Collins’s art. The Fool represents saint, artist and poet – the saviours of life, according to Collins. He always portrays the fool as an innocent figure who, although finding no place in the modern world, has the vision to find fulfilment and eventual reward. Here the Fool is carrying a heart (for love) and an owl (for wisdom and freedom)

When it comes to power and leadership in the church are we confused by worldly perceptions of power and success?

Recently I have heard about arguments amongst leaders about who sits in the “best seats” in the chancel, and there’s real power politics at play in ecclesiastical processions!

If we are entitled (Rev, Reader etc) what are we entitled to? Cases of abuse show how wrong some of us so entitled have been.

What are the qualifications for leadership? And what is our unconscious bias about those qualifications – and how much potential is wasted by those biases?

Justin Lewis-Anthony makes the case that our understandings of leadership are qualified and conditioned by Hollywood and the leadership of those on the “wild frontier” as portrayed by decades of “westerns”. (Donald Trump fits that well.) Lewis-Anthony talks about “the myth of leadership” and describes the way the myth is told.

Someone comes from the outside, into our failing community. He is a man of mystery, with a barely suppressed air of danger about him. At first he refuses to use his skills to save our community, until there is no alternative, and then righteous violence rains down. The community is rescued from peril, but in doing so the stranger is mortally wounded. He leaves, his sacrifice unnoticed by all.

This is the plot of Shane, Triumph of the Will, Saving Private Ryan and practically every western every made. It is the founding myth of our politics and our society. It tells us that violence works, and that leadership only comes from the imposition of a superman’s will upon the masses, and preferably those masses “out there”, not us.

The new archbishop of Canterbury should be a disciple rather than a leader in The Guardian, 4 February 2013

The Bible is very critical of worldly systems of power and leadership. Walter Brueggemann (in Truth Speaks to Power) makes the point that the pharoah is never named in Exodus, but that he is a metaphor representing “raw, absolute, worldly power”. He is never named “because he could have been any one of a number of candidates, or all of them. Because if you have seen one pharoah, you’ve seen them all. They all act in the same way in their greed, uncaring violent self-sufficiency.” Samuel is scathing about the Israelites’ insistence that they be led like the other nations. He knew (1 Samuel 8:11-17) that those sort of leaders are always on the take (sons, daughters, chariots, horses, fields and livestock – everything).

The ways of God are very different to the ways of preferment and career advancement. Paul is amazed when he surveys his fellow disciples. He wrote to the church of Corinth: “Consider your calling. Not many of you were wise according to worldly standards, not many were powerful, not many were of noble birth. But God chose what is foolish in the world to shame the wise. God chose what is weak in the world to shame the strong; God chose what is low and despised in the world, even things that are not, to bring to nothing things that are, so that no human being might boast in the presence of God.” (1 Corinthians 1:26-29).

Similarly Jesus praised God that she had hidden the things of heaven from the seemingly well qualified. “Jesus, full of joy through the Holy Spirit said, “I praise you Father, Lord of heaven and earth, because you have hidden these things from the wise and learned, and revealed them to little children.” (Luke 10:21).

What difference would it make to our CVs if we focused on our foolishness and our weakness? Would it prompt us to realise that power and leadership is found in some very strange places and surprising people? What difference does it make when we recognise that leadership qualifications are the gift of God and that the leadership qualities are love, joy, peace, forbearance, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness and self-control (Galatians 5:22-23) by which measures pharoahs look hopelessly unqualified.

I have recently had the privilege of reading The Bible and Disability edited by Sarah Melcher, Michael C Parsons and Amos Yong. I quickly realised how pervasive disability is and how important a lens it is to view Christian leadership. Under their prompt it is easy to see how “disabled” the people featured in scripture are. Moses was chosen in spite of his speech impediment. Jacob bore his limp with pride that he wrestled with God (and Israel takes its identity and name from that fight). Jesus’ crucifixion was the ultimate disability.

I asked the question on Twitter, “would it make a difference in leadership if we focused on disabilities and vulnerabilities rather than just abilities?” Friend Mark Bennett replied: “In Matthew’s gospel Jesus uses parables so that people hear, “see”, understand anew, overcoming disabilities of preconception, prejudice and fear.” Friend Jenny Bridgman replied: “”What are my blind spots?” is a tough but necessary #leadership question. Some more are: What can someone else do better that I can? How can I free them to do that well? Or even – how do my/our disabilities and vulnerabilities make my/our leadership more effective?”

I suspect that as long as we ignore these questions there will always be “us” and “them” – a few privileged by the powers-that-be working “for” (or even “against” as some sort of pharoah) rather than working and living “with” and in love with others.

PS. I didn’t include the title of Justin Lewis-Anthony’s book because it is so flippin’ long – It is You are the Messiah and I should know: Why Leadership is a Myth (and probably a Heresy) .

Achers of space – sermon notes for Easter 2

Easter 2B – Bromborough

Text – John 20:19-31

Jesus said: “In my house there are many rooms” (John 14:2). That is a mark of his hospitality. It’s the sort of thing that any good host will say to his/her guest. “We’ve got loads of room. We can easily make up a bed.” Good hosts say these things because they want their guests to feel at home – they want their guests to stay with them – they look forward to their company.

As Christians we love what Jesus said. We draw strength from the generous hospitality which says “In my house there are many rooms” – we want to dwell in that house where there is so much room and where there are so many openings.

Today’s Easter gospel is set in one room in which there are an abundance of openings – too many for us to get our heads round.

There’s

- The opening of the door

- The opening of Jesus’ mouth

- The opening of Jesus’ hands and side

Each of them begs for an opening up of ourselves.

In Jesus there is so much opportunity for openings and the resurrection begs of us a reformed hospitality within ourselves. An RSVP is called for from each of us.

A little about each of the openings – the openings could well be a whole sermon series – but today a little on each.

Opening the door

The opening of the door – the disciples had locked themselves in because they were afraid. And Jesus stands amongst them. How did that happen? The open door is a powerful Christian image because of this resurrection appearance.

I have fought a couple of battles in parish ministry. One was about church keys (and who should hold them) and the other was about trying to keep the church open. Like the disciples in today’s gospel the two churches were afraid – they wanted to lock themselves in because they were afraid of their communities.

I don’t know whether you keep this church open. I hope you do. And if you don’t, I hope that you give it some thought allowing Jesus’ words to those first disciples to ring in your ears. “Do not be afraid.” Just imagine the signage – “this church is open” (and all the ambiguity of such a sign!)

There are many metaphorical rooms that we retreat to – in fear, in shame. This gospel story is told time and again to encourage us to open up, to not be so afraid, to not be so ashamed – to let the spaces we move in reverberate to the sound of Jesus’ words.

RSVP

And that takes us to another opening.

Opening his mouth

Jesus’s opening words were “Peace be with you” . Three times in this short passage Jesus greets the disciples with “Peace be with you”. To his anxious and frightened friends he says “peace be with you”. We repeat those words in our greetings in the Peace. “The peace of the Lord be always with you”. (Always try to exchange the peace with at least three people to remember this Easter exchange that we celebrate this morning).

John doesn’t just say that Jesus spoke to his friends. He also tells us that he breathed on them. When he breathed on them they received the Holy Spirit. “The Lord is here. His Spirit is with us.”

Some ancient liturgies included a mouth to mouth kiss as part of the Peace to pass the breath of the Spirit, the breath of the post-resurrection meeting room – a recall of the intimacy of that meeting with the risen Jesus. (See here.)

And what does that make of our hospitality?

RSVP

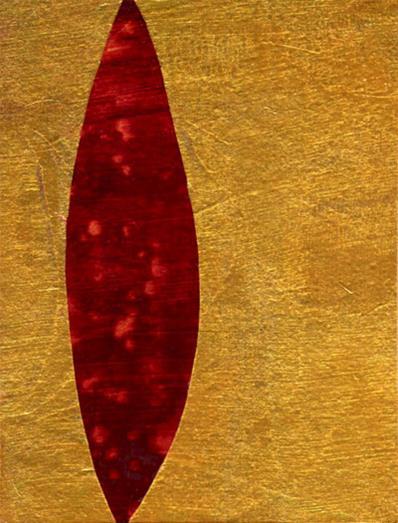

The third opening is that demanded by Thomas, doubting Thomas, Thomas the scientist who wouldn’t believe without seeing the evidence. Thomas said “I won’t believe until I see the mark of the nails in his hands, put my finger in the mark of the nails, and my hand in his side.” And Jesus showed Thomas the nail wounds in his hands, and the spear wound in his side.

I have copied a picture of the wounded side (pictured above) by Jan Richardson from her Painted Prayerbook. It is called “Into the Wound” and I offer it as an invitation for your prayer and wonder. I see it as a tear, as an opening, as a doorway.

Medieval artists gave great attention to Jesus’ wounds. They were often the subject of their art. Such attention for us seems gruesome – but we might be missing an opening.

Eamon Duffy, writing in 15th/16th century England: “the wounds of Christ are the sufferings of the poor, the outcast, and the unfortunate” – according to which acts of charity (foodbanks, nursing, hospitality) become a tending of the living, wounded, corporate body of Christ.

The wound is on his side. Maybe those of us who are on his side can see our own wounds in the wound of Jesus (the ones we’ve inflicted and the ones inflicted on us). Is there an invitation on this door? Is Jesus inviting Thomas, the disciples and all those on his side into the wound, to feel around the space, to know the love, to know the other side?

And is there a reciprocal arrangement, whereby we don’t hide our wounds but invite others into our hurting world so that we might find wholeness and healing? Jesus stands at the door and knocks. If his wound is our way into him, are our wounds his doorway to us?

This is what Jan Richardson writes:

“In wearing his wounds—even in his resurrection—he confronts us with our own and calls us to move through them into new life.

The crucified Christ challenges us to discern how our wounds will serve as doorways that lead us through our own pain and into a deeper relationship with the wounded world and with the Christ who is about the business of resurrection, for whom the wounds did not have the final word.

As Thomas reaches toward Christ, as he places his hand within the wound that Christ still bears, he is not merely grasping for concrete proof of the resurrection. He is entering into the very mystery of Christ, crossing into a new world that even now he can hardly see yet dares to move toward with the courage he has previously displayed.”

Thomas’s RSVP was “My Lord and my God” – his mind blown open, he believed.

Belief in resurrection is often thought of as a rational process. That is how Thomas approached it. But belief isn’t only about our heads. Belief isn’t a rational response but an emotional one. Belief comes from the German word which gives us beloved. “Belief” is “belove” – a believing disciple is a beloving and beloved disciple. When Thomas believes he doesn’t just open his mind, he opens his mouth (as RSVP), his heart and his very gut where all our anxiety and fear find their home.

Jesus opens the room, he opens his mouth, he opens his wounds. We are invited through these open doorways, into a new life that without this gospel would be unimaginable.

Please RSVP.

The image Into the Wound is copyrighted to Jan Richardson and is used with permission – www.janrichardson.com

Leaving childhood: Holy Innocents Day

Today is Holy Innocents Day, when we are called to remember childhood how children have been slaughtered. The focus is on the baby boys Herod slaughtered in Bethlehem at the time of Jesus, but also embraces the children slaughtered throughout history.

Jesus teaches that “unless you change and become like children, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven.” (Matthew 18) This prompts the question about what childhood is. Is it something about vulnerability, dependence, naively and learning. Jesus added the word “humility”. “Whoever becomes humble like this child is the greatest in the kingdom of heaven.”

And then we grow out of childhood, spending a lot of our time bigging ourselves up, taking ourselves out of reach of that kingdom Jesus spoke about.

I am reading organisations don’t tweet, people do by Euan Semple? He seems to suggest that the qualities that make for childhood are the qualities that are needed for leaders and organisations to be successful as he talks about vulnerability and humility in these terms:

“Being open about your failings isn’t everyone’s cup of tea and wouldn’t be acceptable in every workplace, but just a little more openness about your failings in front of your staff might be just be the best way to improve your working relationships. Being seen not to know, and being willing to ask for help, can be the best way to make other people feel valued. It also signals to them that it is OK not to know everything all the time. This creates the sort of culture where people are willing to open up and share what they know to everyone’s mutual benefit.”