We know parable of the Good Samaritan so well we can almost recite it by heart. But maybe that’s the problem. Its edges have worn smooth with repetition, and its challenge no longer cuts as sharply as Jesus intended. What happens when we let it confront us afresh? Here’s a sermon that asks us to imagine hearing it for the first time — and to wrestle with the question that won’t go away: “Who is my neighbour?”.

My customary intro – so customary these days that we could almost do it as call and response.

Here goes: I love preaching that brings scripture back to life.

Call: Do you love preaching that brings scripture back to life?

Response: We do.

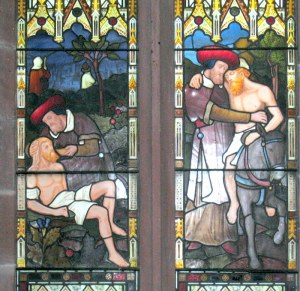

But how do we bring scripture, such as this parable of the Good Samaritan back to life when we’ve worn it smooth with repetition, so familiar that its sharp edge no longer cuts?

Can we imagine the pointedness of the parable for those hearing this for the first time?

Imagine hearing this for the very first time.

Let’s do some word association.

What word do you associate with Samaritan?

What words do you think Jesus’ Jewish contemporaries associated with Samaritan?

Very different sets of word associations

Here’s a bold assertion I read this week: This parable has single-handedly shaped the reputation of the Samaritans. Samaritans stood for everything the Jews hated. In their eyes the Samaritans were despised as the last, the least and the lost. There was no such thing as a “good” Samaritan. Now a Samaritan is someone we can call when we are at the end of our tether. A Samaritan is a first responder – one who runs into trouble to help – unlike those who run away at the first sign of trouble.

But to the question posed by the lawyer, “Who is my neighbour” Jesus casts the main characters as those last, least and lost. There are two main characters.

There is the one attacked by robbers and there is the Samaritan.

It is interesting to note who and what Jesus sees first when he preaches the good news of the kingdom. Jesus sees first not the powerful or the prominent, but the ones left behind,

the last, the least and the lost,

the stripped, beaten, and left for dead,

the wounded and the hated.

The Samaritan and the victim are the ones Jesus sees first when he responds to the lawyer’s question, “Who is my neighbour?”.

They are the ones Jesus “sees”.

And these last, least and lost become the leaders in this discussion about neighbourliness.

Jesus promotes them to be the first to teach the lawyer (and all Jesus’s hearers) a lesson on the question “Who is my neighbour?”

Here are the last.

And here are the first,

way off in the distance,

the priest and the levite,

the first people Jesus’s hearers would have thought should have responded to the stripped, beaten and robbed.

You would expect them to do good.

They are prominent people.

They come first in the public eye, just as they come first in the story Jesus tells.

They are the professionals – the ones who should know the scripture the lawyer quotes: “Love your neighbour as yourself.”

They would have known that as the key to eternal life, but they fail to walk the talk.

I wonder if the lawyer would have done the same – walked by on the other side, failing to walk the talk.

What happens is that the first come last in the eyes of Jesus and the kingdom of God.

They are the ones who become the outcasts by just walking by.

When Jesus preached he said to those who would listen:

Love your enemies,

do good to those who hate you,

bless those who curse you,

pray for those who abuse you. (Luke 6:27-28)

And here today, we hear of a Samaritan,

loving his enemy,

doing good to one, who in all likelihood, hated him

an answer to prayer for the victim, who in all likelihood,

joined in the abusive banter of the time.

The lawyer asked, “who is my neighbour?”

We might ask, “Who is my enemy?”

Enemy is a word of two parts.

There is the ene – meaning not,

and there is the emy,

like the French word ami,

behind which is the Latin word for friend – amicus.

My enemy is literally the one who is not my friend,

not only the one who hates me, curses me and abuses me,

but the one to whom I am nothing, a nobody.

The Samaritan loves his enemy.

This isn’t just about ancient hostilities.

Our world still draws lines between us and them.

Think of the debates around borders and strangers today.

We live in xenophobic times.

Perhaps these times are no different to other times.

Perhaps these times are no different to Jesus’ own times.

Perhaps we’ve always been wary of strangers.

They’re never our friends as long as they are strangers.

They’re the enemy to be kept out.

Behind the lawyer’s question was the idea that there has to be a limit to who our neighbour is.

Probably, like the lawyer, we share the basic assumption that our neighbours are people like us, and people who like us.

But in this parable Jesus not only single-handedly reshapes the reputation of the Samaritan, but he also challenges the scandal of the boundaries we build with our hatred and suspicion.

The lawyer leaves Jesus with the question “Who is my neighbour?”

The question Jesus leaves the lawyer with is, “Will you be a neighbour?”

“Will you go and do likewise?”

“Will you bear to be a neighbour to your enemy – being compassionate, attentive, practical and generous?”

We are left with the same questions.

Will we go and do likewise?

Will we follow the Samaritan’s lead?

Will we cross the road?

Will we engage with the victims of the way things are?

Will we go to the help of the wounded and hated?

Will we attend to their wounds? Will we find help?

Will we just leave them there, beaten and hated?

Will we keep them at arm’s length, as enemy, as “not our friends”?

Or, will we go and do likewise?

Will we love our enemy, doing good to those who hate us, blessing those who curse us, praying for those who abuse us?

Just as Jesus did.

Will we maintain the dividing lines?

Or will we simply be a neighbour, like the Samaritan,

who, unlike the lawyer, never stopped to ask,

“Who is my neighbour?” – as if there needs to be a limit.

PS. I’ve started using ChatGPT to help me prepare for preaching. This week the algorithm threw me a question that stopped me in my tracks:

What if being a neighbour means crossing every line we’ve drawn between “us” and “them”?

PPS It was Jennifer S. Wyant who claims this parable “singlehandedly reshaped the reputation of the Samaritans”.