11th Sunday after Trinity

It’s the Canaanite woman who catches the eye of the church on the 11th Sunday after Trinity (A). “Crumbs!” was what I said when I read the story from Matthew 15 as if for the first time. So Crumbs remains the title for this reflection/sermon.

Crumbs

On the one hand there’s the bread from the feeding of the 5000 (12 baskets worth) and on the other hand there’s the bread from the feeding of the 4000 (7 baskets worth) and between there are the crumbs that are more than enough for the Canaanite woman in this morning’s gospel.

Today’s gospel, showing the growing tension between Jesus and the Pharisees and the great faith of the Canaanite woman is sandwiched between the feeding of the 5000 and the feeding of the 4000.

“Woman, great is your faith” is what Jesus finally notices about the Canaanite woman the disciples wanted to silence, send away and have nothing to do with. She may have only been a dog in the pecking order but she knew that she would be satisfied with the crumbs that fell from the table. Great is her faith in any crumb that falls from the hand of Jesus.

In contrast the disciples thought that they would never have enough to feed the five thousand (as well as women and children) or the four thousand (as well as women and children). They say before the feeding of the 5000: “We have nothing here but five loaves and two fish”. And before the feeding of the 4000 they want to know “where are we to get enough bread in the desert to feed so great a crowd?” Jesus had to show them. They would never have believed that there would be 12 baskets left over from feeding 5000, or 7 baskets left over from feeding 4000.

I dare say that most of us fall into the same boat as those first disciples. Common sense is enough to know that five loaves and two fish are never going to be enough for 5000, and seven loaves and few small fish are never going to be enough for 4000. Can we ever believe that so little can go so far?

We perhaps have little faith in such miracles.

In the same boat, when the storm was blowing a gale, Jesus notes the “small faith” of his disciples. “Why are you afraid, you of little faith?” (Matthew 8:26). Seemingly they had such little faith in him that they thought they were all going to drown together. It almost seems as if this is what Jesus called his disciples; “You of little faith”.

In the sermon on the mount, Jesus said “if God so clothes the grass of the field, which is alive today and tomorrow is thrown into the oven, will he not much more clothe you – you of little faith?” (Matthew 6:30)

When Peter realised he wasn’t walking on water Jesus reaching out to rescue him said, “You of little faith, why did you doubt?”

When the disciples were worried that they had forgotten to take bread with them Jesus said, “You of little faith, why are you talking about having no bread?” (Matthew 16:8)

You might expect those first disciples to have great faith but they remain the ones of little faith. They have “little faith” and are slow to understand. In today’s gospel Jesus asks Peter, “Are you still without understanding?”

As for the religious leaders, it would be reasonable to expect that they would have great faith. These are the religious leaders of Israel we are talking about. But they have no faith in Jesus at all. “Blind guides” and “hypocrites” is what Jesus calls them. Their concern was the keeping of rules – all 613 of them were to be kept at any cost. They were offended by Jesus’ attitude toward washing hands before eating and were more concerned about what came out of people’s bottoms than mouths. (If everyone had to wash their hands before eating then the 5000, the 4000 (plus women and children) would have remained starving. The feeding would have been impossible.)

The only faith the Pharisees had was in a god who demanded obedience and required people to do x, y and z and follow every letter of the law. They had no faith in a gracious God. They looked for offences. Tragically there are still religious leaders who have no faith in a gracious God and who are looking for offences. They too are blind guides and hypocrites. And they are frightening.

Jesus had to go a long way to find great faith. He had to leave Israel. He left that place and went away to the district of Tyre and Sidon. Tyre and Sidon are a long way out. They’re in what is now known as Lebanon. They were beyond the pale. Jesus probably went there with his disciples to get away from the pressure building from the Pharisees – he was wanting some space.

And then this Canaanite woman came to him.

She knew precisely who he was and she knew exactly what he could do.

He was the Lord and son of David.

He was the one who would show her mercy.

He was the one to help her daughter.

But she was a woman.

She was a foreign woman, a despised Canaanite.

And she shouted.

The disciples wanted Jesus to send her away.

They didn’t want to hear anything from her.

What a good job Jesus resisted, because otherwise he would never have discovered her great faith.

And nor would we.

It was only through what some people now call “radical listening” that Jesus found what he probably wasn’t expecting to find. Radical listening is a discipline which allows the other person their say and hearing. The discipline involves removing our personal biases which bias us to listen to the people we are most used to hearing, and like hearing from. It’s about giving the mic to those who are often silenced and taking it away from those who jealously guard it.

Jesus allowed her the mic, and Matthew’s gospel provides the amplifier, amplifying her “great faith”. This Canaanite woman was a faith leader for Jesus and for Matthew. I wonder why she hasn’t remained so. Her “great faith” is what Jesus was working towards for his disciples as he continued to teach them about the way of faith and the graciousness of God.

Her “great faith” is such a contrast to those “of little faith” and those who had no faith in Jesus. She echoes the prophetic voice which insists that no faith is to be found where it is expected – for example, in the Temple, or the religious leaders, the Pharisees and scribes and the keepers of tradition. No “great faith” is to be found in Israel. Only some “little faith” – which little faith is carefully nurtured by Jesus.

Great faith is found elsewhere, where it is not expected, beyond the pale, in foreign bodies. It is found through radical listening which shushes our biases so that we hear the voice of others (perhaps for the first time), their stories, their journeys, their faith. We might be outraged like the disciples (those of little faith). That woman did SHOUT, but people need to shout if they’re not being heard, particularly when they so need help. They often need to get their rage out, which may come across as outrageous.

At our moment in history it is refugees who are shouting and struggling to be heard. It is the planet which is shouting, struggling to be heard – their claims being too easily dismissed as outrageous, their voices being too easily silenced. We need to be disciplined to hear those made to suffer in silence.

The Canaanite woman, our great faith leader, is key to the door that opens up mission everywhere. Matthew lets his gospel rest with the great commission to go and make disciples of people everywhere, baptising them in the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit, and opening the way of faith to them.

The mission of God has always been a mission to overcome boundaries. We’ve heard that this morning from our reading from the prophet Isaiah in the promise to bring all the foreigners who join themselves to the Lord to the holy mountain, to make them joyful in the house of prayer, which will be forever known as a house of prayer for all people, says the one who gathers those cast out by Israel.

The story of the Canaanite woman is sandwiched between the feeding of the 5000 and the feeding of the 4000, between the feeding of the 5000 tired, radical listeners and the crowd of 4000 including the lame, maimed, blind and mute on whom Jesus had compassion.

She was prepared to eat the crumbs which fell from the table.

In communion we join her, her great faith.

In communion we join her to the 5000 and the 4000.

In communion we join her great faith even with the little faith we may have in the gracious God Jesus is showing us.

Isaiah 56:1, 6-8

Thus says the Lord:

maintain justice, and do what is right,

for soon my salvation will come,

And my deliverance be revealed.

And the foreigners who join themselves to the Lord,

to minister to him, to love the name of the Lord,

and to be his servants,

all who keep the sabbath and do not profane it,

and hold fast my covenant –

these I will bring to my holy mountain,

and make them joyful in my house of prayer;

their burnt-offerings and their sacrifices

will be accepted on my altar;

for my house shall be called a house of prayer

for all peoples.

This says the Lord God,

who gathers the outcasts of Israel,

I will gather others to them

besides those already gathered.

Matthew 15:10-20, 21-28

Then he called the crowd to him and said to them, ‘Listen and understand. It is not what goes into the mouth that defiles a person, but it is what comes out the mouth that defiles.’ Then the disciples approached and said to him, ‘Do you know that the Pharisees took offence when they heard what you said?’ He answered, ‘Every plant that my heavenly Father has not planted will be uprooted. Let them alone; they are blind guides of the blind. And if one blind person guides another, both will fall into a pit.’

But Peter said to him, ‘Explain this parable to us.’

Then he said, ‘Are you still without understanding? Do you not see that whatever goes into the mouth enters the stomach, and goes into the sewer? But what comes out of the mouth proceeds from the heart, and this is what defiles. For out of the mouth come evil intentions, murder, adultery, fornication, theft, false witness, slander. These are what defile a person, but to eat with unwashed hands does not defile.’

Jesus left that place and went away to the district of Tyre and Sidon.

Just then a Canaanite woman from that region came out and started shouting, ‘Have mercy on me, Lord, Son of David, my daughter is tormented by a demon.’ But he did not answer her at all. And his disciples came and urged him, saying, ‘Send her away, for she keeps shouting after us.’ He answered, ‘I was sent only to the lost sheep of Israel.’ But she came and knelt before him, saying, ‘Lord, help me.’ He answered, ‘It is not fair to take the children’s food and throw it to the dogs.’ She said, ‘Yes, Lord, yet even the dogs eat the crumbs that fall from their master’s table.’ Then Jesus answered her, ‘Woman, great is your faith! Let it be done for you as you wish.’ And her daughter was healed instantly.

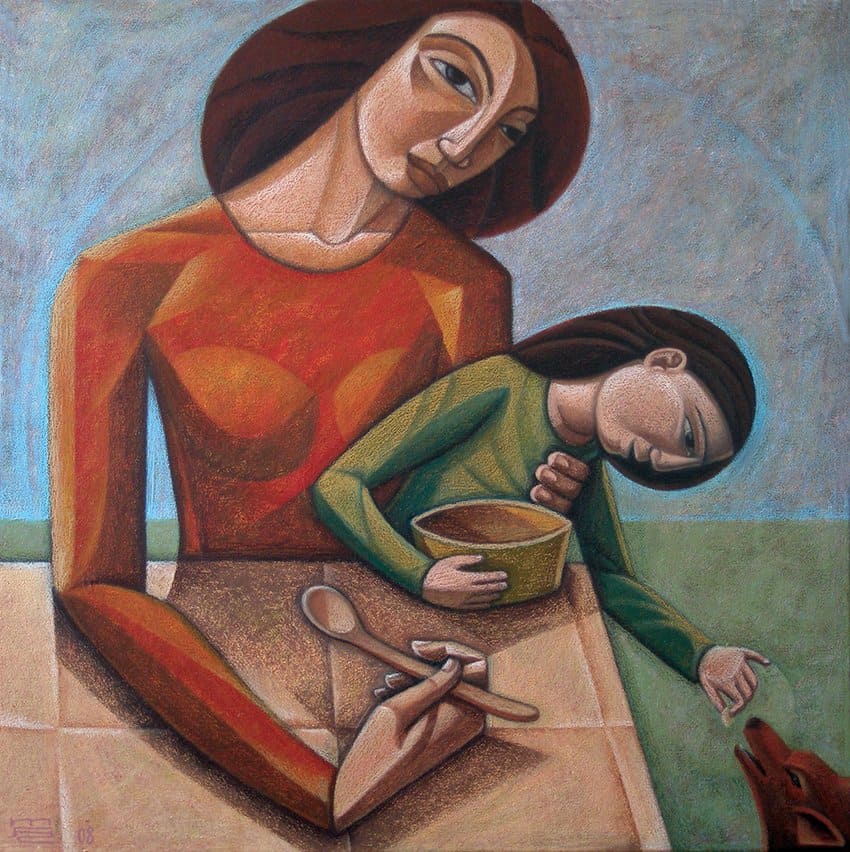

Image credit: Michael Cook, “Crumbs of Love” http://www.hallowed-art.co.uk/twelve-mysteries-2/