Preached on the Fourth Sunday of Advent, this sermon sits with Matthew’s telling of Jesus’ birth at midwinter — when the light is weakest and hope can feel thin. It explores how God chooses to begin again not in tidiness or certainty, but in the mess, risk, and vulnerability of ordinary human lives.

This is how the birth of Jesus the Messiah came about.

These are the words Matthew uses to describe the birth of Jesus.

This is how it happened.

This is how it began.

When I say,

“these are the words Matthew uses,”

what I really mean is,

“this is how we have translated the words Matthew wrote.”

Matthew wrote in Greek,

and the key word in that opening sentence is a Greek word we know very well, the word genesis.

Τοῦ δὲ Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ ἡ γένεσις οὕτως ἦν· μνηστευθείσης γὰρ τῆς μητρὸς αὐτοῦ Μαρίας τῷ Ἰωσήφ, πρὶν ἢ συνελθεῖν αὐτοὺς εὑρέθη ἐν γαστρὶ ἔχουσα ἐκ πνεύματος ἁγίου

Genesis.

Beginning.

Origin.

The start of something that will change everything.

Matthew is not just telling us how a baby was born.

He is taking us back to the very beginning.

Back to the beginning of the world.

Back to the beginning of God’s work with humanity.

Back to what begins with Jesus.

It is no accident that we hear this reading now

— on the shortest day of the year,

at midwinter,

when the light is at its thinnest and the night feels longest.

Because beginnings often come like that.

Quietly. In the dark.

When the ground looks bare and the fields seem empty.

When nothing much appears to be happening at all.

This is when God makes his presence felt.

Matthew takes us back to a beginning that looks very small.

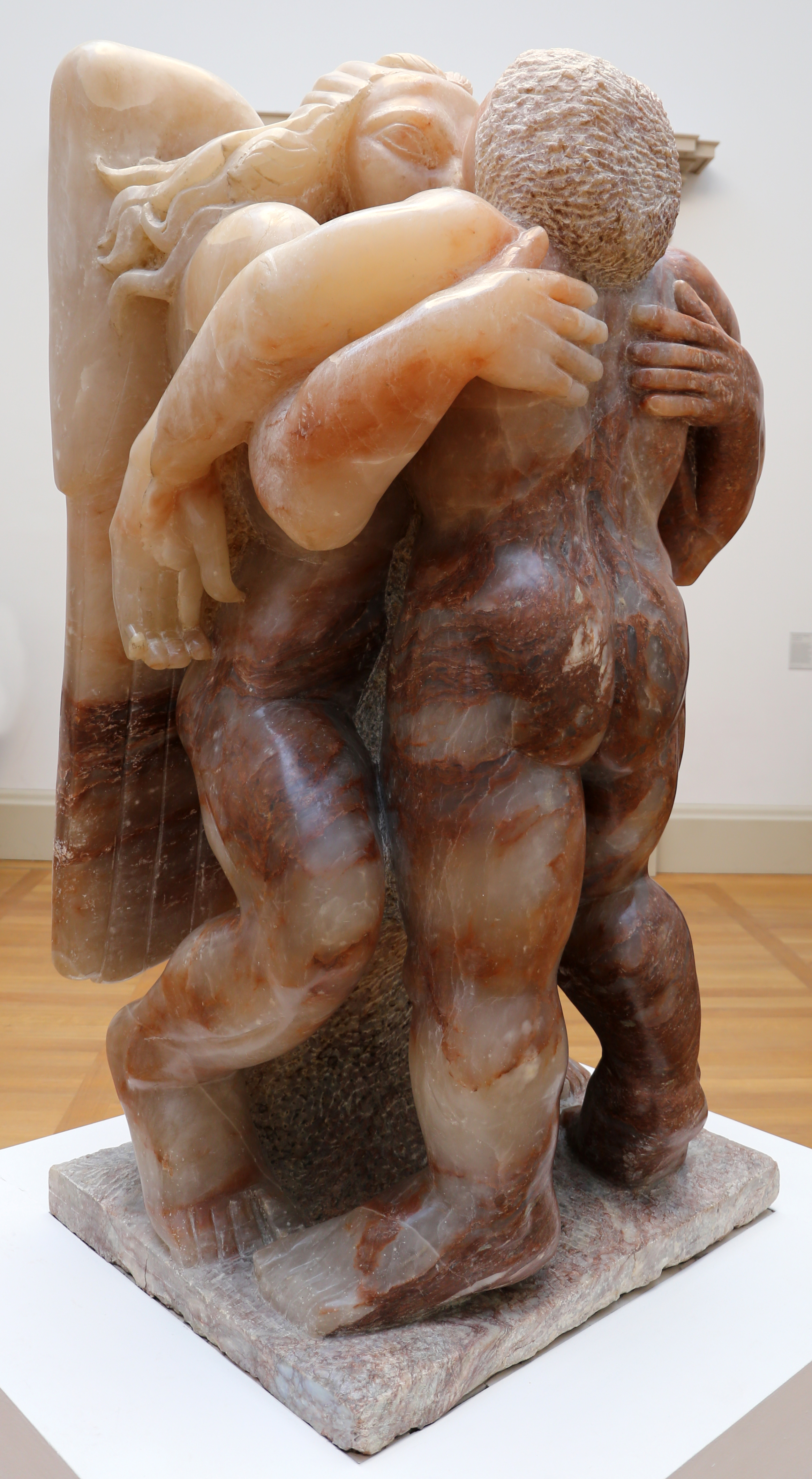

Just as in Genesis, there is a young boy and a young girl.

But they’re not Adam and Eve. They are Joseph and Mary.

Ordinary people with complicated lives.

Adam and Eve walked freely with God.

They had no backstory.

No reputation to protect.

No neighbours to worry about.

But Joseph and Mary live in a world where things are already tangled.

Mary is pledged to be married, but not yet married.

Joseph is a good man, but suddenly faced with a situation that could cost him his standing, his future, his place in the community.

This is not a beginning without consequences.

This is a beginning that arrives already burdened.

And God does not wait for a cleaner moment.

God begins again here — not in freedom, but in constraint;

not in clarity, but in confusion;

not in daylight, but in the deepening darkness.

This is how the birth of Jesus comes about.

Not by sweeping the mess away, but by entering it.

Not by restoring the world to how it once was,

but by beginning something new within the world as it is.

in a teenage love story,

in the vulnerability of these two youngsters.

Both are vulnerable.

Mary is pledged to Joseph but not living with him.

She’s pregnant. People are going to talk.

If she’s not been with Joseph, who has she been with?

She is at risk of being shamed, isolated and abandoned –

a public disgrace.

Joseph is vulnerable too.

He has the reputation of being a righteous man

because he tries to do the right thing.

If he stays with Mary he risks his reputation

(costly to his business and his standing).

If he leaves her she is exposed.

There is no clear path.

And here God begins.

In this mess framed by confusion, risk and fear.

God begins again by stepping into lives that are already complicated

— and trusting them with something holy.

Genesis does not wait for spring.

It begins when the light is weakest

in the midst of winter,

and slowly grows from there.

When God begins here, it is not with explanations.

Matthew tells us that Joseph makes up his mind.

He decided what he will do.

And then God speaks.

Not in public,

not with spectacle,

but in the dark night,

In a dream.

The angel does not tidy the situation.

He does not remove the risk.

He does not promise that everything will be all right.

He says only this:

Do not be afraid to take Mary as your wife.

Do not be afraid to stay.

Do not be afraid to be seen.

Do not be afraid to let your life be changed.

And then Matthew gives the child a name.

Emmanuel.

God with us.

Not God with us when the mess is sorted.

Not God with us when the rumours stop.

Not God with us when life feels safe again.

But God with us, here,

in confusion,

in vulnerability,

in teenage love that chooses faithfulness over self-protection.

When Joseph wakes up,

he does what the angel has told him.

And that is how the story moves forward.

Not through certainty.

Not through control.

But through trust.

And this is the genesis Matthew chose to share with his readers,

how God begins his work

these days that are long with darkness.

He begins with a boy and a girl,

with ordinary people inspired to trust.

Slowly, quietly, faithfully the light begins to grow.

This is how the birth of Jesus comes about.

God begins again –

with us –

in the dark.

NOTE

I make no secret of the fact that I’m greatly helped by AI when preparing sermons. Used well, it doesn’t write sermons for me, but helps me listen more closely — to Scripture, to season, and to the lives of the people I’m preaching among. This sermon is better than it would otherwise have been, and I’m grateful for the help.