Read gently my friend.

Facebook friend, Josh Askwith, has just heard the book of Genesis read straight through. What struck him was not the violence, nor the intrigue, nor the strangeness. It was something else. He posted this:

“I was struck by how gently it ends.”

And that’s got me thinking. Gently. That is not the adjective most people reach for when describing the Old Testament.

His comment landed on top of a conversation I had recently with someone who confessed that she “struggles” with the Old Testament. She is not alone. Many Christians speak of it as though it were a necessary preface to the real story — darker, harsher, spiritually inferior. The implication is often unspoken but clear: the Old Testament is something Jesus saves us from.

I wonder how much of that instinct has been formed not simply by careful reading, but by centuries of misreading — by a habit of exaggerating the discontinuity between Old and New, of distancing Jesus from his Jewish roots, of quietly rendering Israel’s scriptures obsolete. When we treat the Old Testament as primitive or problematic, are we inheriting interpretative habits shaped, at least in part, by anti-Jewish assumptions?

And then Genesis ends — not with thunder, but with tenderness.

Joseph forgives his brothers. Revenge is refused. Fear is met with reassurance. “You meant it for harm,” he says, “but God meant it for good.” The story closes not in triumph but in trust — a coffin in Egypt, waiting for promise. It is strangely, stubbornly gentle.

But the gentleness is not softness. It is shaped by a deeper pattern running all the way through the book.

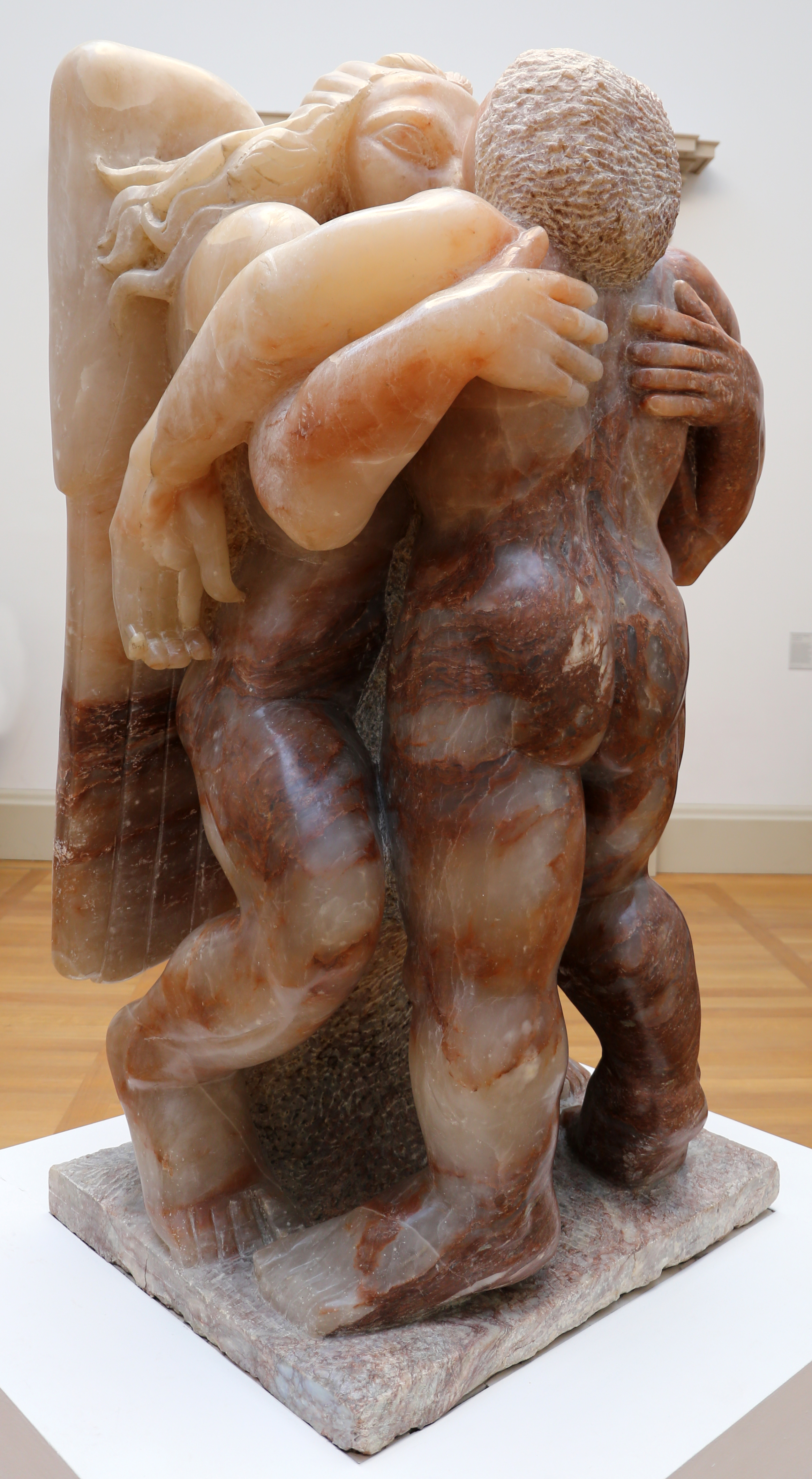

Near the end, in Genesis 48, we are given an image that feels almost like a summary of everything that has gone before. Jacob — old now, frail, nearing death — is brought Joseph’s two sons to bless. Manasseh, the firstborn, is positioned at Jacob’s right hand. Ephraim, the younger, at his left. Everything is arranged according to custom, according to entitlement, according to the straight lines of inheritance – so that Manasseh will be blessed first and Ephraim last. That is the way of the world.

But then Jacob crosses his hands.

The right hand rests on the younger boy. The left on the elder.

Joseph tries to correct him. It must be a mistake. But Jacob refuses. The crossing is deliberate.

It is hard not to smile at the irony. The name Jacob is bound up with grasping and twisting — the heel-grabber, the supplanter. The one who once twisted his way into stealing a blessing from his brother Esau, now twists his own arms to give one. The old twister twists again — but this time not to steal, not to secure advantage for himself, but to bend the future toward the overlooked.

Genesis has been rehearsing this pattern from the beginning. Abel over Cain. Isaac over Ishmael. Jacob over Esau. Joseph over his brothers. And now Ephraim over Manasseh.

This is not randomness. It is theology.

God’s blessing does not run along the straight lines of primacy, status, or expectation. It bends. It crosses. It interrupts the obvious.

For those who are first, secure, established, this is unsettling. For those who are second, small, despised, or displaced, it is life.

Read this way, Genesis is not primitive folklore. It is dangerous scripture.

It belongs to the Torah — to a people who would know slavery, exile, homelessness; who would know what it is to be second best. It is instruction for living under empire. It is a memory bank for those whose lives do not follow the straight lines of power. Again and again it whispers: the story is not over when you are overlooked. The blessing may yet cross in your direction.

No wonder such texts can be domesticated. If the Old Testament can be caricatured as angry, obsolete, or morally inferior, its critique of hierarchy is neutralised. If it is reduced to a foil for a gentler New Testament, its radical edge is blunted.

But Jesus does not stand over against this story. He stands within it.

When he speaks of the last being first and the first last, he is not inventing a new moral universe. He is speaking Torah-deep truth. When Mary sings of the proud scattered and the lowly lifted, she is echoing the long music of Israel. When the kingdom is announced as good news to the poor, it is not a departure from Genesis but its flowering.

The rule of the kingdom of God crosses old hierarchies. It must – if the second best, the left out and despised are to find favour.

That does not mean the first are hated or the strong despised. The point is not revenge. The crossing of hands is not retaliation; it is freedom. God is not bound by our ranking systems. Blessing is not the private property of the powerful.

Perhaps that is why Genesis ends gently. Because beneath its betrayals and famines and rivalries runs a deeper current of mercy — a God who keeps bending history toward life.

A God who crosses his hands.

And for those who have lived too long on the left side of the room – left behind, left out – that is not merely interesting theology. It is hope. It is radical gentleness.